Reading Assignment

- SECS, Chapter 6: Sun Earth Geometry (scan through the entire chapter first.)

Please scan all of Chapter 6 right away, to get an initial overview of the role of angles and time together with the relative positions of the Sun, Earth, and the SECS that your client would like to install. We use several angles throughout this chapter (check back to the Table of Angular Symbols anytime, also found in the textbook Ch. 1). We also use a whole lot of dense equations. Don't be intimidated by the equations; they are all based on the trigonometry for a spherical surface, and we will break them down in chunks in this lesson. Just take note of them and keep reading. Take a few notes in the margins as you go!

In this first assignment, we are going to get familiar with the angular relations between the Earth and the Sun, and the relation of those angles to things like Seasons! You are all familiar with the concept that winters are cold, and summers are hot, but why??

Keep an eye out for the cosine projection effect. This is something that we often wish to minimize by tilting our solar energy conversion systems up toward the predominant diurnal (daily) arc of the Sun averaged over the year.

Earth's Rotation

As we have seen in our reading, the Earth rotates with a roughly constant speed, so that every hour the direct beam (a ray pointing from the surface of the Sun to a spot on Earth) will traverse across a single standard meridian (standard meridians are spaced 15° apart). The implications are that the unit of one hour is equivalent to the rotation of Earth 15 degrees. When Earth rotates such that the beam of the sun shifts +1° of longitude from East to West: it takes 4 minutes of time.

- 1 h = +15° Earth rotation

- 4 min = +1° Earth rotation

Wild fact: a time zone change of one hour is really just 15 degrees of separation between standard meridians.

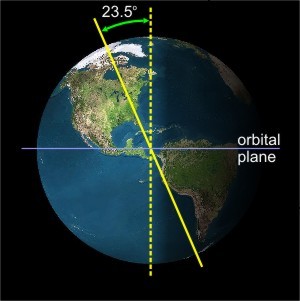

The axis of rotation of the Earth is tilted at an angle of 23.5 degrees away from vertical, perpendicular to the plane of our planet's orbit around the sun.

The tilt of the earth's axis is important, in that it governs the warming strength of the Sun's energy. The tilt of the surface of the Earth causes light to be spread across a greater area of land, called the cosine projection effect.

Cosine Projection Effect

When you tilt a surface away from a beam of light, you spread the same density of light across a larger area. Recall that irradiance is in units of W/m2, so a larger denominator means a smaller value of irradiance, right?

Explore the concept of the cosine projection effect in the following experiment.

Self-Check

This links directly with Chapter 6: Experiment with a Laser of SECS.

Watch the video of the virtual flashlight below and then answer the questions.

Video: Light intensity experiment using a flashlight (0:17)

In this video, changes made to the angle of the flashlight affect light intensity. The shallower the angle, the more the light spreads out, resulting in a lower intensity.

Seasons and the Cosine Projection Effect

The sun is about 93 million miles away from the Earth (equivalent to ~150 million km). That is so far away that the photons from solar irradiation effectively travels in parallel rays. So, unlike the flashlight experiment, the tilt of the sun has no bearing on the intensity of the radiation reaching the Earth's surface. Instead, we find that the Earth's tilt controls the intensity of irradiation and the seasons.

Keep in mind that the Earth's axis points to the same position in space (toward the North Star, Polaris). As the Earth travels in a near spherical (a very small eccentricity into an ellipse) orbit around the sun, the Northern Hemisphere can be tilted toward or away from the sun, depending on its orbital position.

SPRING: (Image of the tilt of the earth in the spring) In this configuration, the earth is not tilted with respect to the sun’s rays (The earth in this picture is actually tilted towards you as indicated by the fact that you can see the North Pole – green dot). Therefore, radiation strikes similar latitudes at the same angle in both hemispheres. The result is that the radiation per unity area is the same in both hemispheres. Since this situation occurs after winter in N. Hemisphere we call it spring, while in the S. Hemisphere it is autumn. This occurs on March 21.

SUMMER: (Image of the tilt of the earth in the summer) When the N. Hemisphere is tilted towards the sun, the sun’s rays strike the earth at a steeper angle compared to a similar latitude in the S. Hemisphere. As a result, the radiation is distributed over an area which is less in the N. Hemisphere than in the S. Hemisphere (as indicated by the red line). This means that there is more radiation per unity area to be absorbed. Thus, there is summer in the N. Hemisphere and winter in the S. Hemisphere. This situation reaches a maximum on June 21.

AUTUMN: (Image of the tilt of the earth in the autumn) In this configuration the earth is not tilted with respect to the sun’s rays (The earth in this picture is actually tilted towards you as indicated by the fact that you can see the North Pole – green dot). Therefore, radiation strikes similar latitudes at the same angle in both hemispheres. The result is that the radiation per unit area is the same in both hemispheres. Since this situation occurs after summer in the N. Hemisphere we call it autumn, while in the S. Hemisphere it is spring. This occurs on September 21.

WINTER: (Image of the tilt of the earth in the winter) When the N. Hemisphere is tilted away from the sun, the sun’s rays strike the earth at a shallower angle compared to a similar latitude in the S. Hemisphere. As a result, the radiation is distributed over an area which is greater in the N. Hemisphere than in the S. Hemisphere (as indicated by the red line). This means that there is less radiation per unit area to be absorbed. Thus, there is winter in the N. Hemisphere and summer in the S. Hemisphere. This situation reaches a maximum on December 21.

Self-Check

Click on "Summer" in the above animation. When the Northern Hemisphere tilts toward the sun, the irradiation has a lower angle of incidence, meaning more photons strike a smaller area during the daytime. Answer the following questions for yourself. If you have any questions, please post to the Lesson 2 Discussion Forum.

- What happens to the Southern Hemisphere?

- What is the correlation with concentrated sunlight and the seasons?

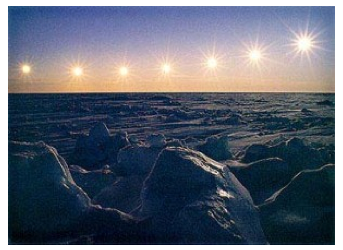

- What happens beyond the Arctic Circle, which spans from about 66.5 degrees latitude to the North Pole?

Now, answer the same questions for autumn, spring, and winter.

Forecasters and meteorologists use different criteria to determine the "meteorological seasons." For example, meteorological winter in PA runs from December 1 to Feb 28/29, a period that statistically includes the three coldest months of the year. This is also centered on a time about 25 days after the Winter Solstice.

Meteorological summer runs from June 1 to August 31, a period that includes the warmest three months of the year. Again, this is a period centered about 25 days from the Summer Solstice.

As one more example, review Pittsburgh's plot of annual average high temperatures. The maximum daily temperature occurs in late July, long after the summer solstice.