5.4 Curvature Effect: Kelvin Effect

Let’s look at curvature effect first (see figure below). Consider the forces that are holding a water drop together for a flat and a curved surface. The forces on the hydrogen bonding in the liquid give a net inward attractive force to the molecules on the boundary between the liquid and the vapor. The net inward force, divided by the distance along the surface, is called surface tension, σ. Its units are N/m or J/m2.

If the surface is curved, then the amount of bonding that can go on between any one water molecule on the surface and its neighbors is reduced. As a result, there is a greater probability that any one water molecule can escape from the liquid and enter the vapor phase. Thus, the evaporation rate increases. The greater the curvature, the greater the chance that the surface water molecules can escape. Thus, it takes less energy to remove a molecule from a curved surface than it does from a flat surface.

When we work through the math, we arrive at the Kelvin Equation:

where esc is the equilibrium vapor pressure over a curved surface of pure water, es is the equilibrium vapor pressure over a flat surface of pure water, σ is the water surface tension, nL is the number of moles of liquid water unit per unit volume, R* is the universal gas constant, and rd is the radius of the drop. Note that es is a function of temperature while esc is a function of temperature and drop radius. Because σ and nL are relatively weak functions of temperature and R* is constant, it is useful to combine them as follows:

where we have used 0 oC values for σ (0.0756 J m–2) and nL (5.55 x 104 mol m–3).

Since the evaporation is greater over a curved surface than over a flat surface, at equilibrium the condensation must also be greater over a curved surface than over a flat surface in order to keep condensation equal to evaporation, which is required for saturation (i.e., equilibrium). Thus, the saturation vapor pressure over a curved surface is greater than the saturation vapor pressure over a flat surface of pure water.

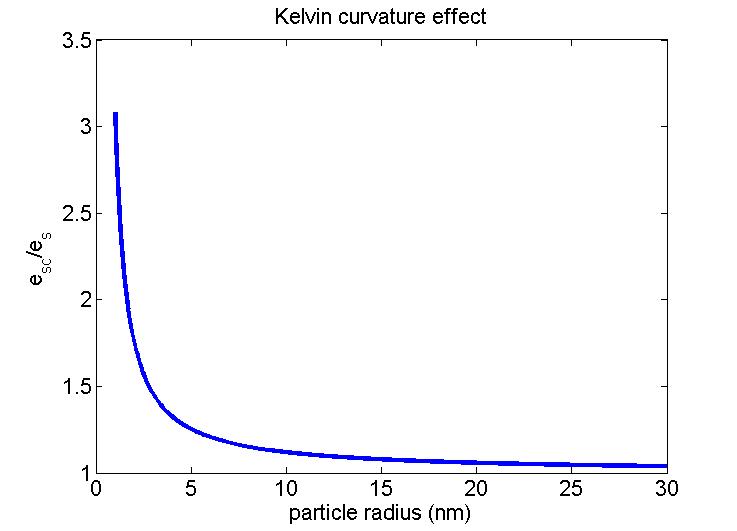

When we plot this equation, we get the following figure:

Note the rapid increase in equilibrium vapor pressure for particles that have radii less than 10 nm. Of course, all small clusters of water vapor and CCN start out at this small size and grow by adding water.

The Kelvin Equation can be approximated by expanding the exponential into a series:

Summary

Cloud drops start as nanometer-size spherical drops, but the vapor pressure required for them to form is much greater than es until they get closer to 10 nm in size. The Kelvin effect is important only for tiny drops; it is important because all drops start out as tiny drops and must go through that stage. As drops gets bigger, their radius increases and esc approaches es.

So, is it possible to form a cloud drop out of pure water? This process is called homogeneous nucleation. The only way for this to happen is for two molecules to stick together, then add another, then another, etc. But the radius of the nucleating drop is so small that the vapor pressure must be very large. It turns out that drops probably can nucleate at a reasonable rate when the relative humidity is about 440%. Have you ever heard of such a high relative humidity?

So, the lesson here is that homogeneous nucleation is very unlikely because of the Kelvin effect.