Earth Structure

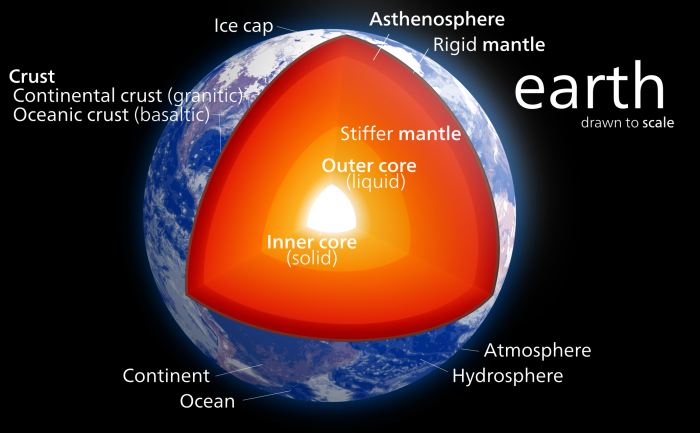

Crust

At the scale of the whole Earth, the crust is a relatively thin, solid outermost layer that ranges in thickness. The thickest part of the crust exists in areas with mountain ranges and may be as much as 100 km thick in some locations but, generally, the crust is between approximately 30 and 35 km. Below the oceans, the crust is much thinner, averaging about 5 km. Two fundamental types of crust are recognized: Continental Crust, which is below continental land masses, and Oceanic Crust, which is below the oceans.

Mantle

Below the crust is a much thicker layer called the mantle. Because of a higher abundance of dense minerals, the mantle is much denser than the crust. At shallow levels just below the crust, the mantle is rigid; whereas at deeper levels, although the mantle is still solid, it has the ability to flow slowly like taffy or putty. Because the rigid part of the upper mantle behaves mechanically like the overlying crust, the two are lumped together and referred to as Lithosphere. It is the lithosphere of the planet that breaks by fracturing, and it is the lithosphere that is broken into a series of tectonic plates. These plates are able to move very slowly across the hotter and partially molten underlying material that deforms by flowing and is referred to as the asthenosphere. It is the flow of the very hot asthenosphere that helps to deform and drive motion of the overlying lithospheric plates.

Core

From a depth of approximately 2,000 km to the center of the Earth at a depth of 6,378 km is the very dense and very hot metallic core.