Yellowstone is Shaking - Real-world Applications: Yellowstone and Earthquakes

Yellowstone: for many people, the name is synonymous with national parks. Yellowstone was the first national park, for a while it was the biggest (at approximately 60 miles by 60 miles—100 km by 100 km—it is still a big one), and it is widely considered to be the best. You could probably identify a dozen features or more that, separately, would merit protection by a national park. The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone is a great chasm cut through volcanic rocks that have been “cooked” by hot water and steam circulating through them, in the process gaining the yellow color that gave the park its name. The Canyon contains two large waterfalls (rather unimaginatively called the Upper and Lower Falls), where the river plunges over more-resistant rocks. Mammoth Hot Springs is a mountain being turned inside-out, with acidic hot-spring waters dissolving caves underground, bringing the dissolved limestone to the surface, and depositing some of it as gleaming terraces. Specimen Ridge is home to at least 20 petrified forests complete with petrified roots, standing one on top of the other, from roughly 40 million years ago. Volcanic ash and debris flow buried the standing trees, and chemical reactions caused the silica in the ash to move into the wood, replacing it (a subject for much later in the course). A new forest grew and was buried, and this was repeated 20 or more times.

The biggest draws at Yellowstone are the thermal features. Various lines of evidence indicate that there is a body of melted rock (magma) under the park, now up towards the northeast side. The rocks under most of the park are anomalously hot at shallow depth. In addition, the park receives abundant rainfall and snowfall. The water from rain and melted snow circulate deeply through rocks broken by numerous earthquakes, and the water is heated from below. In some places, the water is heated all the way to steam, which emerges from holes known as fumaroles. In other places, hot water bubbles to the surface in beautiful springs. If the bubbling action mixes in enough mud, then paint pots, mud pots or mud volcanoes develop.

Sometimes, cold water on top holds hot water down, with the pressure preventing the boiling of the hot water in a pressure-cooker effect. Eventually, a little boiling manages to expel a little of the water above, reducing the pressure, allowing more boiling, and a geyser erupts. Geysers require heat, water, and a tight, tough plumbing system to hold the hot water and withstand the high pressures. The volcanic rocks of Yellowstone are rich in silica, which is dissolved and re-precipitated by the hot waters to seal cracks in the rocks, helping produce geysers. Perhaps half of the world’s geysers are in Yellowstone, including the largest and most spectacular ones. Yellowstone also is noted for many waterfalls besides those in the Canyon, for a number of other interesting features, and for abundant wildlife, which we'll visit later in the course.

Yellowstone itself is centered on the Yellowstone Caldera, a collapse feature related to three great volcanic eruptions, or periods of eruptions. The caldera, roughly 50 x 30 miles (80 x 50 km), includes Yellowstone Lake but extends well beyond it. (No lake in the nation is both higher and larger than Yellowstone Lake, yet it is only a piece of the caldera.) The eruptions occurred roughly 1.8, 1.2, and 0.6 million years ago. Each of these eruptions moved roughly 1000 times more material than did the Mt. St. Helens eruption of 1980 that we will discuss soon; thick deposits erupted from Yellowstone are known from the Badlands region of South Dakota. The erupted material that spread across South Dakota was removed from a magma chamber, and after removal, the “top fell in” to create the large depression that is the caldera.

Yellowstone has many lessons to teach us. (Some year, it would be fun to have a course on the geology of Yellowstone alone, and we certainly could fill a semester.) The size of the Yellowstone eruptions is of considerable interest, especially considering the likelihood that they will recur. Here, we wish to use Yellowstone to introduce earthquakes.

European exploration of the Yellowstone region probably began with “mountain man” John Colter during his return from the Lewis and Clark expedition in 1806, although Native Americans had used the region for thousands of years before. Colter brought back fantastic tales of the region, which were largely dismissed because they seemed impossible. Other travelers, and especially Jim Bridger in the 1850s, returned with similar tales, which also were discounted, in part because Bridger was a bit of a tall-tale teller. He is credited with stories of petrified birds sitting on petrified trees singing petrified songs (an exaggerated description of Specimen Ridge), of rivers that ran so fast they became hot on the bottom (the Firehole River, which actually has hot springs on the bottom), of trying to shoot an elk and missing because a mountain of glass was in the way (Obsidian Cliff, where rapidly-cooled volcanic rocks have made a glass called obsidian, which was mined, shaped, and traded by the Native Americans), and more.

To separate fact from fancy, the Washburn expedition from Montana (Washburn was surveyor-general of the Montana Territory) visited the region in 1870, and first developed the idea of a national park. The government-sponsored Hayden expedition of 1871 provided scientific documentation of the wonders of Yellowstone, supported by the artwork of Thomas Moran and photography by W.H. Jackson, which convinced Congress to found the park in 1872.

While in the park, the Washburn party felt earthquake activity. Breaks in recent stream and glacier deposits showed the geologists of the party that faulting had occurred recently, and motion on faults produces earthquakes. Since then, modern monitoring equipment has detected numerous quakes in the area.

On August 17, 1959, a Richter-magnitude 7.5 quake occurred, centered near the northwestern boundary of the park. Many of the geysers were changed, and a new one (Seismic Geyser) suddenly began to erupt. The ground over the quake (at the epicenter—the place above the center of the quake) was broken, with one side dropping roughly 6 feet (2 meters) relative to the other side, and with a little twisting and turning causing even larger drops in some places. A large landslide was triggered, burying a campground, damming the Madison River to form Quake Lake, and burying many highways. 28 people were killed. Some survivors had their clothes literally torn off by the immense blast of wind pushed out of the way by the huge landslide. The Old Faithful Inn was evacuated, and the west entrance to Yellowstone closed. The University of Utah’s Seismograph Station has a nice summary of the press reports. You may find it interesting to search for and read the report from the Billings Gazette that a beauty pageant was going on in the historic Inn with 800 people watching, and that “Moments after the queen had been crowned and she was walking down the aisle to the plaudits of the crowd, the first, mighty shock hit. Everyone in the place dashed for the door.”

Elastic Rebound Theory

An earthquake is just the shaking of the ground, and many things can cause earthquakes. Much effort has been devoted to detecting underground nuclear tests by the earthquake waves produced. Mining cave-ins, conventional explosions, and other events can cause earthquakes. The deepest earthquakes, which are very rare but often among the biggest ones, may have a phase-change or "implosion" origin, which we'll discuss later.

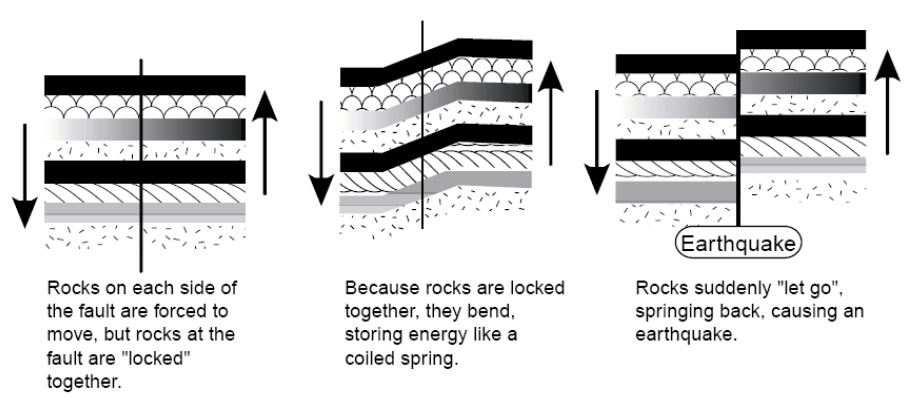

However, most earthquakes are produced by elastic rebound. We’ve already seen that rocks are moving around on the planet and that the pull-apart action has allowed Death Valley to drop down. We will see that other motions occur as well, with one group of rocks moving past another. Where rocks are warm and soft, they flow. Where cold and hard, they cannot flow.

Consider, for example, two large pieces of rock, such as southwestern California and the rest of the state. The southwestern part of the state, from Los Angeles to San Francisco, and the adjacent ocean floor are moving northwest relative to the rest of the state. The break separating the different parts is called the San Andreas Fault. (Both sides are moving westward, but the southwest side has an additional bit of northwesterly movement relative to the northeast side. Faults may go east-west, or north-south, or any other direction, may be vertical or angled, and the rocks may move vertically or horizontally or in-between across the fault.) The forces that move the rocks are huge and applied over large areas so that far from the fault the motion is smooth. But at the fault, rough patches can get stuck against each other and become locked for a while. The rocks then bend. This bending is elastic—it can spring back. Eventually, the stress on the rough spots becomes too great, the fault “lets go”, and the bent rocks “spring back”. The springing back is very rapid, in the same way as for a spring or a rubber band. Displacements of several feet (more than a meter) or more are possible in much less than a second. A building sitting on the rocks near the fault can be subjected to very large accelerations and may fall apart.

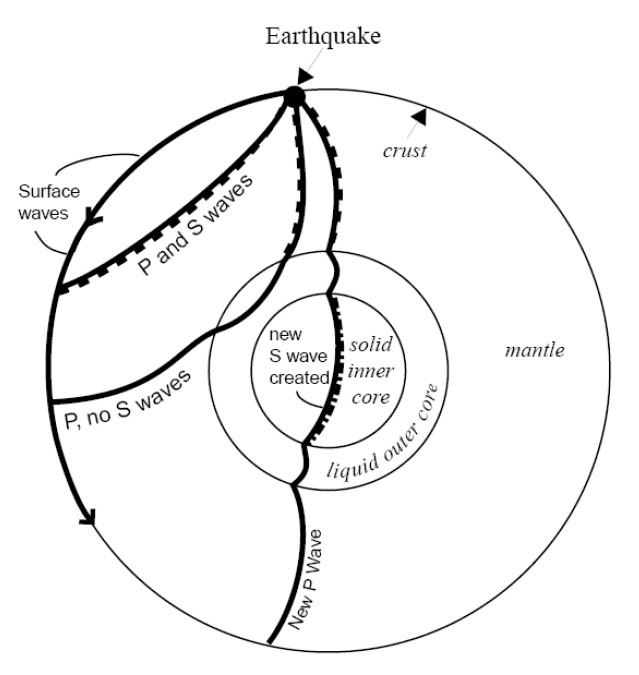

Such an earthquake will shake rocks beyond a fault. This is achieved through seismic waves—one piece of rock pushes another next to it, which pushes one next to it, and so on. Two major types of seismic waves are P or push, and S or shear. The P-wave is the ordinary sound wave. It represents a push-pull in the direction the wave is moving. A P-wave moving to the north will shake a mineral grain north-south-north-south. An S-wave moves slower than the corresponding P-wave. When an S-wave moves to the north, the mineral grains are shaken east-west-east-west or up-down-up-down (or some combination). A shear wave is similar to the wave you generate by shaking a rope. A piece of the rope moves up and down or back and forth, but the wave moves along the rope. The “wave” at football games is the same way—you stand up and sit down, but the wave moves along the bleacher bench. A P-wave may start a building shaking in one way, and then the S-wave hits the building and starts shaking it a different way, making the building more likely to break and fall down. (Earthquakes also make surface waves, which move more slowly than shear waves and go along the surface of the Earth like wind-driven waves on the ocean, rather than going through the Earth the way P- and S-waves do. The surface waves can also contribute to breaking buildings.)

S-waves don’t travel through liquids at all. (Wiggle one piece of liquid to the side, and the moving piece slides freely past the next piece rather than wiggling it.) Recall that earlier we claimed that the outer core of the Earth is liquid. You may have asked, “How does anyone know that?” The answer is that, after a really big earthquake, P-waves can be detected all over the Earth. But S-waves are missing across the Earth from the quake, in places reachable only by passing through the core, as shown by the figure. So we know that the outer core is liquid because it transmits P-waves but not S-waves. And the outer core is nearly spherical, because no matter where an earthquake occurs on the planet, there is a zone on the other side of the Earth in which S-waves are absent. (Learning that the inner core is solid is tougher; one of the pieces of evidence is based on wave conversions. The P-wave that passes through the outer core loses some energy in making an S-wave when the P-wave hits the inner core; this S-wave passes through the solid inner core, making a new P-wave when it hits the liquid outer core again, and that P-wave travels on to the surface. The delay associated with the slower motion of the S-waves allows this to be figured out. But don’t worry about wave conversions, or the other evidence for a solid inner core, in an introductory course such as this one.)

Where Quakes Occur

Earthquakes, as noted above, occur where rocks are moving past other rocks. We have seen that this happens where rocks are being pulled apart, as in Death Valley, because the breaks often are angled rather than vertical, and the upper side slides down over the lower. We will see that there are other situations in which rocks are being pushed together, or that rocks are sliding past each other as at the San Andreas Fault, and these also can make quakes. This mostly occurs near plate boundaries. Volcanoes can cause small-to-medium-sized quakes as well, when moving melt pushes rocks aside or leaves spaces into which rocks fall.

Quakes also occur at weak spots in continents. Often, when a continent is splitting open at a spreading ridge, the tear assumes a 3-armed form, something like the Mercedes-Benz logo. (Poke your finger through a piece of paper and you’ll often get the same thing.) Two arms then grow into a spreading ridge that forms an ocean, and the third arm fails. Major rivers often form in such failed rifts. When the Americas split from Africa and Europe as the Atlantic Ocean grew, failed rifts became the river beds of the Amazon, the Niger, and the Mississippi. You open a fast-food ketchup packet by tearing at a little notch cut in the foil, because the notch weakens the foil. If the notch isn’t there, you may have to poke a fork through or end up saying bad words, because the packet is much harder to tear without the pre-existing notch. In the same way, earthquakes can occur at the tips of failed rifts, which are the “notches” in the “foil” that is the lithosphere of the Earth. Some of the largest quakes known to have occurred in the U.S. were located at the northern tip of the rift along which the Mississippi flows, near New Madrid, Missouri. Quakes also are known from an old weakness near Charleston, South Carolina.

Size of Earthquakes

There are several ways to measure earthquake size. The commonest is the Richter scale, a measure of how much the ground shakes during a quake. Richter developed a logarithmic scale—a magnitude 2 quake shakes the ground 10 times more than does a magnitude 1 quake, and a magnitude 3 quake shakes the ground 10 times more than does a magnitude 2 or 100 times more than does a magnitude 1. You may think of the number of zeros after the 1: if the ground motion of a magnitude 1 quake is 10 (you can choose the units you use, or the distance from the quake at which you measure, to get a motion of 10), then at the same distance from the quake in the same units, a magnitude 2 moves the ground 100 (two zeros), a magnitude 3 moves the ground 1000 (three zeros), a magnitude 0 moves the ground 1 (zero zeros), a magnitude -1 moves the ground 0.1, and so on.

The ground motion can be measured with special instruments called seismographs. Scientists usually look at either P-waves or surface waves to get the size of the quake. The motion must be corrected for distance from the quake; the farther away from the quake your seismograph is, the smaller the ground motion you will measure. Distance can be calculated from the difference in arrival time between the first P-wave and the first S-wave from the quake to reach the instrument, using the difference in speed between P- and S-waves, or by timing the arrival of the earthquake waves at three or more stations, and determining where the quake must have been so that the waves arrived earlier at this station than at that one.

A Richter magnitude 1 quake is just big enough to feel if you are standing on the ground very near where the quake occurs. Magnitude 3 or 4 quakes are usually strong enough to convince some people to call the police (although it is not obvious what these people want the police to do), and magnitude 5 quakes usually cause some damage. The largest known quakes, around 9, each release about 10,000 times the energy of the first atomic bombs.

Small quakes are very common and large quakes rare—one or more years may pass between one magnitude-8 quake and the next one anywhere on the planet. Approximately, each increase in magnitude of 1 causes a 10-fold decrease in frequency of occurrence. But, moving the ground 10 times more takes about 30 times more energy, so most of the energy release and the damage is by the few big quakes rather than by the many little ones.

Predicting Earthquakes

A tremendous amount of effort has gone into trying to predict earthquakes. This is because they are so destructive of life and property. Seventeen quakes are estimated to have killed more than 50,000 people each, and the worst, in Shaanxi, China in 1556, is estimated to have killed over 800,000. (In the U.S.A., the worst death toll was 503 in the San Francisco quake of 1906.) The magnitude 9.0 Tohoku earthquake in Japan in 2011 killed over 15,000 people, although the toll would have been far, far worse if the Japanese had not put so much effort into making strong buildings and otherwise planning to reduce the damages. Earthquakes usually kill by dropping pieces of broken buildings on people, but also by triggering tsunamis (big waves) or landslides, and by breaking gas lines or other things that cause fires.

The easiest way to “predict” quakes is to identify those places where quakes are likely to occur. This can be done from historic records, and from prehistoric geologic evidence. A pattern of landslides of a single age in a region, or of drowned forests related to land subsidence, may indicate the effects of an earthquake. Once people know where quakes are likely, appropriate zoning codes for buildings can be enacted. Spending a million dollars on special engineering for a building to survive quakes is wise indeed near the San Andreas Fault, and really helped Japan, but may not be necessary in State College, Pennsylvania, where big quakes are considered to be highly unlikely.

Other ideas have been advanced for predicting quakes. One is to use patterns of seismicity. If one section of a fault has had a quake every 20 years for the last century, you might expect another quake 20 years after the most recent one. Also, a fault that is slipping and moving may have lots of little quakes, whereas a locked fault that is building to a big quake may have no little quakes. So you could use such a no-quake “seismic gap” in predictions. Such a pattern—historical repeats and a seismic gap—was used recently to predict a quake near Parkfield, CA on the San Andreas Fault. The prediction failed miserably. The possible explanation is that there are many faults in that part of California, and several big quakes occurred on faults near the San Andreas shortly before the expected quake. These certainly perturbed the state of stress at Parkfield, at least delaying its quake. (The other quakes allowed rocks to move, and even caused some faults to run backwards compared to their normal behavior for a while, taking the load off and delaying the next quakes.) This illustrates the difficulty of predicting quakes. Perhaps, if the motions of all of the important blocks were monitored, one could model the whole system and do a better job of predicting where stresses are accumulating. Such work is ongoing, but results are not yet in.

Even if pattern-predictions of earthquakes can be made to work, the predictions are unlikely to be precise enough to really tell us what we want. Knowing that a quake will occur sometime in the next few years, or even the next few days, does not allow us to get people out of old buildings, off bridges, etc., during the quake. The best hope for predictions within hours or minutes is to find premonitory events. As the stresses build toward failure, rocks may begin to crackle, groundwater may move around in the cracks so that water rises in some wells and falls in others, electric signals may be given off by the cracking rocks, and animals may act strangely. The difficulty is that groundwater rises and falls in wells for many reasons, strange actions in an animal may indicate bad feed, mating season, or any number of other causes, and other premonitory events of earthquakes also have non-earthquake causes. The subtle clues to an earthquake may be recognized using 20/20 hindsight, but no one has figured out how to read them in advance. The possibility is there, though, waiting for brilliant insights and hard work by some interested researchers. (After a big quake, lots of people show up claiming that they predicted it, but none of these “predictions” has ever been verified. And, many people, including some scientists, have made predictions of particular earthquakes to come, but again, these predictions have not proved to be useful.)