The Paris Climate Agreement

The Paris Accord is a really big deal. This global climate agreement brokered by the United Nations and signed in December 2015 by some 195 countries went into effect in October 2016. A key goal of the accord is for all member countries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to keep global temperature rise below 2o C of pre-industrial levels (measured in 1880). This is a threshold level above which most scientists agree that the impacts of climate change will be catastrophic, including flooding of large coastal cities by sea level rise, brutal heat waves, and droughts that could cause widespread starvation in developing countries. The agreement also lays the groundwork for countries to strive to reduce emissions to keep temperature increase below 1.5o C or 2o C. 1.5o C is considered to be the best case scenario given that we are currently at 1.1o C above 1880 levels, and it would need very drastic emissions cuts very quickly. Above 1.5o C low-lying island nations in the Pacific and Indian Oceans would likely end up underwater. The agreement also acknowledges that 2o C is a more likely warming target. As we've seen before, this is a significant amount of warming but much more favorable than the 3 or 4oC which would produce catastrophic climate effects.

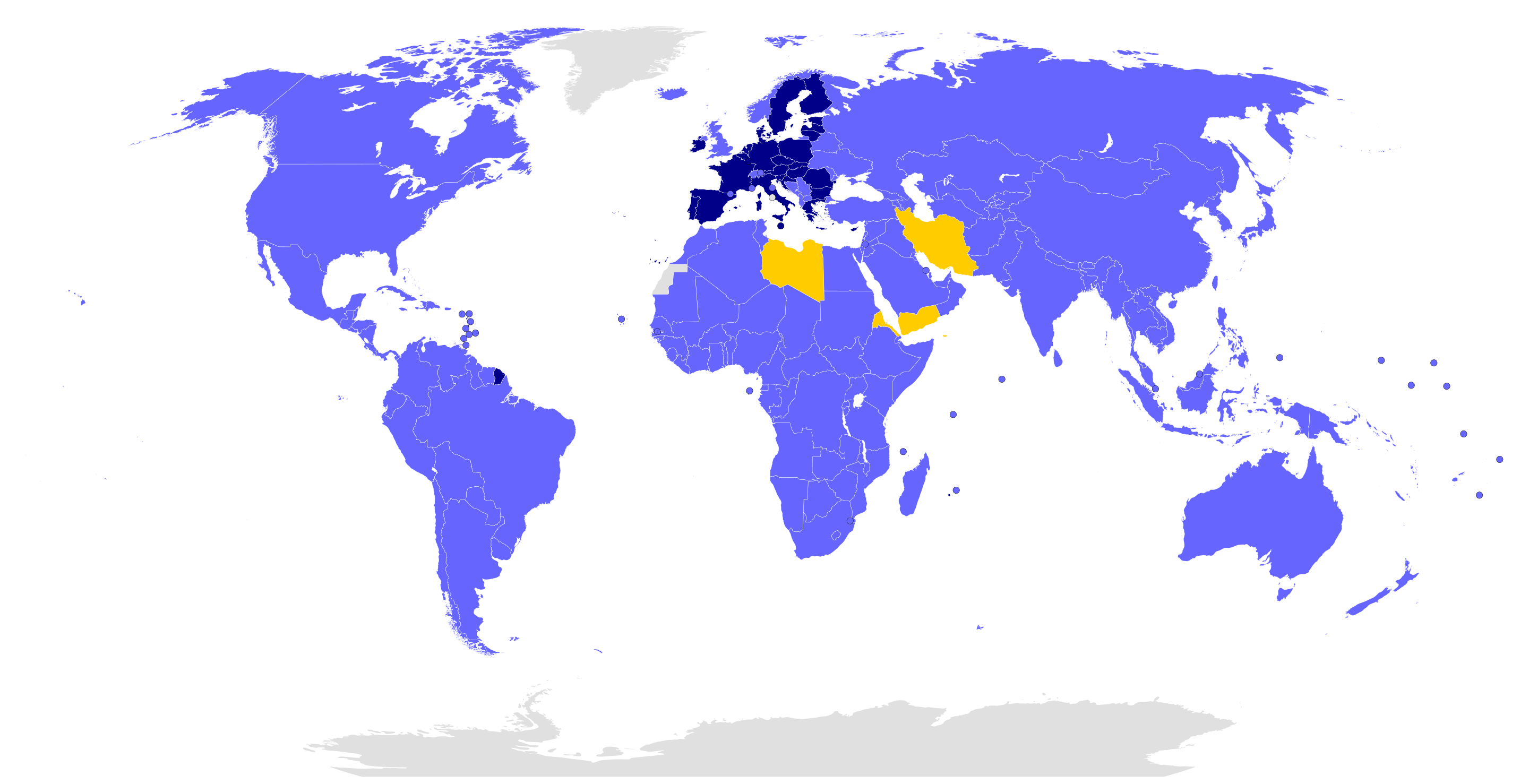

This image is a world map highlighting specific regions in different colors, likely indicating participation in a global agreement, organization, or event. The map uses color coding to differentiate between regions with distinct statuses.

- Map Type: World map

- Color Coding:

- Dark Blue:

- Most of Europe

- Represents a specific group, possibly indicating full participation or membership

- Yellow:

- Middle Eastern countries: Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and parts of North Africa (Libya, Egypt)

- Represents a different status, possibly indicating partial participation or a specific regional grouping

- Light Blue:

- Rest of the world (North and South America, most of Africa, Asia, Australia)

- Represents another status, possibly indicating non-participation or a different level of involvement

- Dark Blue:

- Additional Features:

- Country borders are outlined in black

- Oceans are in black, and polar regions (Arctic and Antarctic) are in white

The map visually distinguishes between regions with different levels of involvement in a global context, with Europe in dark blue, parts of the Middle East and North Africa in yellow, and the rest of the world in light blue.

There have been numerous previous climate agreements in the past, most notably the 1997 Kyoto Protocol that laid out stringent emissions targets for the countries that signed on. One of the reasons the Paris Accord was adopted by so many nations (only Syria and Nicaragua did not sign initially, but both now have) is because the impacts of climate change are becoming increasingly urgent. Although 127 countries signed on to Kyoto, the US did not.

The second reason the accord was so widely adopted is that the emission targets are voluntary, set by the individual countries based on what they believe is feasible. For example, the US’s goal was to reduce emissions by 26 percent by 2025. Once a country sets its target, it is required to abide by it and present supporting monitoring data. A country can change targets every five years. The downside of the flexibility is that many experts believe that with current targets, 1.5o C is impossible, 2o C is highly unlikely and 3o C is more realistic. So, countries will have to reduce emissions radically and rapidly to stave off the highly adverse impacts of climate change.

Two other key provisions of the Paris Accord is that richer developed countries have made a financial commitment to help poorer developing nations meet their targets, although there were no firm amounts in the agreement. President Obama pledged $2.5 billion to this fund while he was in office, but only $500 million was paid. Another key provision is that the agreement recognizes and addresses deforestation as a key element of emission reduction and for countries to use forest management strategies as part of their emissions goals. In fact at the climate summit in 2021, 100 countries including Brazil where deforestation has been particularly devastating, agreed to stop deforestation entirely by 2030, which would be a major step forward.

For the US, one of the key components of the emissions reduction strategies was the Clean Power Plan, introduced in 2014 under President Obama. The CPP set out to reduce emissions from electrical power generation by 32% based on the reduction of emissions from coal-fired power plants and the conversion to renewable sources of energy including wind, solar, and geothermal.

So, the strength of the Paris accord is that it is voluntary, highly transparent and collaborative. The downside is that it is voluntary! The general fear is that the agreement may not go far enough, fast enough.

Back and Forth History of the Paris Agreement

However, that said, this is by far the most widely adopted agreement and the global scope is a massive accomplishment. So, it was a major disappointment on June 1st, 2017 when President Donald Trump signaled that the US would withdraw from the Paris Accord in 2020, the earliest time the US could pull out under the agreement guidelines. The fear is that if the US, the second largest producer of carbon, does not abide by its emissions goals, other countries might not as well. Trump's reasons were largely economic, that the conversion to renewable energy would be too expensive and hinder the bottom line of businesses, especially the fossil fuel industries. However, as we will see in this class, conversion to renewables has begun and has the potential to be a very large and highly profitable business. Moreover, cities, states, and businesses themselves, especially those in the northwest and on the west coast are already committed to reducing emissions, so at least part of the US will continue to collaborate with other countries to address the critical issue of climate change.

Trump's overall strategy involves defunding and repealing the Clean Power Plan, which happened in 2019. It was replaced by the Affordable Clean Energy Rule, which was invalidated by the courts in 2021.

Former President Biden reentered the Paris Agreement on 19 February 2021 and set even more ambitious US emissions targets than those originally agreed upon. The Inflation Reduction Act passed in 2022 includes $369 billion to help individuals, communities, and industries switch to renewable energy. This would help the US meet its Paris targets, and possibly more importantly, the legislation shows important leadership on the international stage. However, fast forward to 2025 and President Trump signed an executive order to leave the Paris agreement on 2026. if this happens the US will be one of four countries outside of the agreement along with Iran, Libya and Yemen. After this announcement Former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg committed to funding the US financial commitments to the agreement. So stay tuned on that. Also in 2025 most of the clean energy funding for the Inflation Reduction Act was repealed by Congress, a majot setback for the US meeting its Paris goals.

We will refer to the Paris Agreement in the remainder of the course. In this module, we discuss how models simulate the climate of the future. In closing, remember the 2oC number, it's going to come up over and over again.