Coral Reefs

Introduction

Coral reefs have existed for hundreds of millions of years and provided a habitat for some of the richest diversity on the Earth’s surface. They are the marine version of tropical rainforests. Reefs harbor a slice of the marine food chain, all the way from tiny autotrophic protistans (autotrophs fix carbon through photosynthesis) to large, predatory fish. Hundreds of millions of humans live near reefs and receive important resources from them. Reefs host productive fisheries; they also provide protection to low-lying coastal areas from storms and are vital for a number of key habitats, including mangrove forests.

Examples of Reef Corals

Examples of Deep Water Corals

The organisms that have constructed reefs, largely corals, have evolved over time, and with that change so have the locations of reefs and the dynamics of the reef community changed. Over their long history, reefs have had several intervals of crisis; in particular, they almost ceased to exist at the Permian-Triassic boundary, where over 90% of marine species became extinct, and during the Cretaceous about 100 million years ago when giant clams took over these structures for several tens of millions of years. Both of these ancient times were potentially characterized by ocean acidification. However, reefs have been remarkably resilient over geologic time and generally have been able to adapt to environmental change. For example, as we will see in Module 10, they are able to grow fast enough to keep up with very rapid rates of sea level rise.

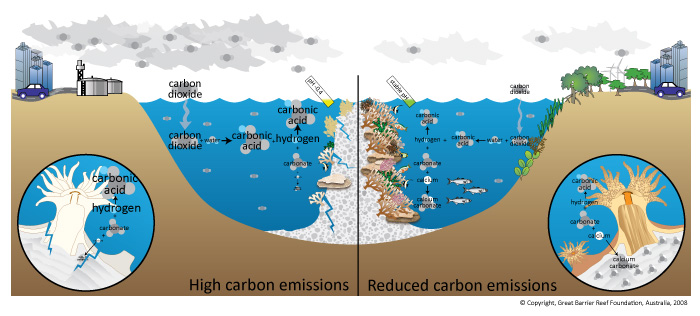

A diagram comparing the effects of high carbon emissions versus reduced carbon emissions on ocean chemistry, created by the Great Barrier Reef Foundation, Australia, in 2008. It features a cross-sectional view of a coastal environment with land on both sides and the ocean in the center. On the left, under "High carbon emissions," factories and vehicles emit carbon dioxide (CO2), which dissolves into the ocean, forming carbonic acid (H2CO3) that dissociates into hydrogen ions (H+) and bicarbonate ions (HCO3-), reducing carbonate ions (CO3^2-) and damaging coral structures. On the right, under "Reduced carbon emissions," wind turbines and vegetation indicate lower CO2 levels, resulting in less carbonic acid formation, higher pH (8.2), and healthier coral growth. A magnified inset on each side shows the contrast in coral health.

- Left Section (High Carbon Emissions)

- Label: High carbon emissions

- Features: Factories, vehicles, and a person on land

- Emissions: Carbon dioxide (CO2)

- Ocean Process:

- CO2 dissolves into water → Carbonic acid (H2CO3)

- Dissociates into Hydrogen ions (H+) and Bicarbonate ions (HCO3-)

- Reduces Carbonate ions (CO3^2-)

- pH: Lower (not specified)

- Visual: Damaged coral, sparse marine life

- Inset: Magnified view of eroded coral with labels for carbonic acid, hydrogen, and carbonate

- Right Section (Reduced Carbon Emissions)

- Label: Reduced carbon emissions

- Features: Wind turbines, vegetation, and a car on land

- Emissions: Reduced CO2

- Ocean Process:

- Less CO2 → Less carbonic acid formation

- Higher Carbonate ions (CO3^2-) availability

- pH: 8.2

- Visual: Healthy coral, thriving marine life

- Inset: Magnified view of healthy coral with labels for carbonic acid, hydrogen, and calcium carbonate

- Ocean Environment

- Color: Blue water with green and brown shading for coral and land

- Position: Central area between land sections

- Chemical Labels

- Carbon dioxide (CO2)

- Carbonic acid (H2CO3)

- Hydrogen ions (H+)

- Bicarbonate ions (HCO3-)

- Carbonate ions (CO3^2-)

- Calcium carbonate (CaCO3)

- Land Features

- Left: Industrial landscape with buildings and vehicles

- Right: Renewable energy landscape with turbines and trees

With this background, recent human activity has placed reefs in as precarious a position as at almost any time in their history. The last fifty years have witnessed an extremely dramatic decline in the health of many of the major reefs around the world, including reefs of the Caribbean, the Bahamas, and the Florida Keys as well as those in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, including the massive Great Barrier Reef of Australia. The outlook for these rich and complex ecosystems is about as bleak as any ecosystem on Earth. As it turns out, ocean acidification is one of several environmental threats to reefs, with warming, pollution, overfishing and physical destruction all exerting major threats to reefs in the future. As we will see, acidification is perhaps the greatest of all of these threats long term.