Harmful Algal Bloom 101

Dinoflagellates are a group of microscopic single-celled organisms or protists that are dominantly autotrophic (i.e., primary producers). Interestingly, many species are also mixotrophic, having the ability to ingest their prey as a source of energy. Some species are entirely heterotrophic, lacking chloroplasts or plastids, and have been termed carnivorous. In fact, there have been reports in the scientific literature that some species have the ability to consume fish after having paralyzed them with neurotoxins. These claims are controversial but have given dinoflagellates a near-mythical reputation among the oceanic plankton.

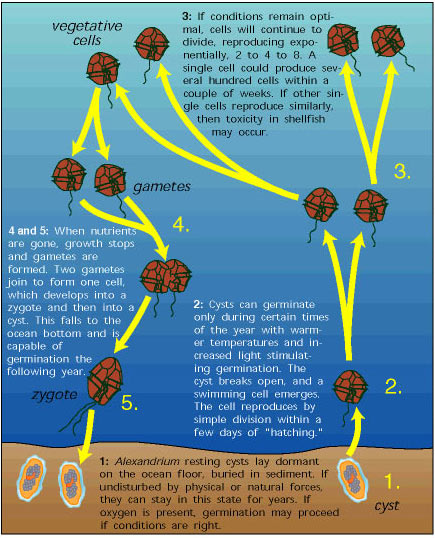

Life Cycle of a Single Algal Cell

- For certain red tide species, a resting cyst lays dormant on the ocean floor, buried in sediment. If undisturbed by physical or natural forces, it could stay in this state for weeks, months, even years.

- Warm temperatures and increased light cause the cyst to germinate. It breaks open and a swimming cell emerges. The cell reproduces by simple division within a few days of "hatching."

- If condition remains optimal, cells will continue to divide, reproducing exponentially 2 to 4 to 8 to 16. A single cell could produce 6000 to 8000 cells within one week.

- (and 5.) When nutrients are gone, growth stops and gametes are formed. Two gametes join to form one cell, which develops into a zygote and then into a cyst. This falls to the ocean bottom, ready to germinate.

Diatoms and dinoflagellates are most common in the coastal oceans but also have the ability to live in freshwater environments and in intermediate salinity environments where fresh and marine waters mix in estuaries. They are the most prolific group of primary producers in the ocean. Dinoflagellates have a highly complex life cycle that consists of an alternation between a motile stage and a resting or cyst stage. In short, dinoflagellates enter the resting stage via sexual reproduction when conditions in the surface ocean are not suitable for them to thrive. They can remain dormant for weeks, months or years before they “excyst,” when surface conditions improve, reproduce vegetatively, and populate the surface ocean. Excystment and repopulation are triggered by changes in temperature, light, or oxygen levels or even resuspension of cysts by storms. Dinoflagellates generally thrive when nutrient levels are elevated, and, under conditions of extremely high nutrient levels, cell division can be so rapid that extremely high cell counts (millions of cells per milliliter of seawater) are reached, resulting in red tides. The cyst stage acts as a very effective mechanism for seeding blooms.

Dinoflagellates

The following video summarizes the life cycle of the dinoflagellates.

Video: Life Cycle of the Dinoflagellates (1:27)

TIM BRALOWER: The basis of red tides are dinoflagellates. Dinoflagellates are incredible organisms that have the ability to reproduce extremely rapidly, producing large amounts of toxin that compose red tides. The original stage of the dinoflagellate is the cyst. The cyst is the stage that resides in the sediment, and it can stay in this location for many years. When there's a trigger in the overlying water column, often increase in nutrients or increase in temperature, the dinoflagellate will excyst into the vegetative stage.

The vegetative stage is a stage that reproduces asexually and this reproduction can occur extremely rapidly, producing many millions of cells in the overlying water column in a short period of time. When conditions change, often decreasing amounts of nutrients or lower light levels, cooling temperatures, the dinoflagellate will reproduce sexually producing gametes. And these gametes will form the zygote stage that will then, in turn, form the cyst stage which will fall to the bottom of the ocean and reside in the sediment once again, for years, until conditions change again.

Dinoflagellates have a broad range of different ecologies. As we saw earlier in the module, they can be endosymbionts of corals, facilitating calcification in the host colony. They have this same role in foraminifera and radiolarian, a group of siliceous zooplankton.

Diatoms

Diatoms are autotrophic protists that produce a delicate, microscopic test of opaline silica.

They are non-motile, and, for most of their life cycle, they reproduce asexually. Many nearshore diatom species also have a resting stage akin to the dinoflagellates, allowing them to exit the surface zone when conditions are unfavorable for their growth. This may occur in winter when surface waters are cold or at times when nutrients are depleted. The resting spore stage actually may resemble the vegetative stage of dinoflagellates. Like the dinoflagellates, diatoms are able to reproduce extremely rapidly by simple cell division, and this allows them to rapidly dominate the surface ocean when nutrients are readily available.

Video: Diatom Life Cycle (1:38)

TIM BRALOWER: Normal diatom reproduction is dominated by asexual or vegetative cell division. In this type of reproduction, an individual diatom will divide, and the new diatom cells will reside in two new diatom shells, one which has one valve from the parent, and one which has the other valve from the parent. Because this is the way that the cell divides and the shells form, over time the shells become smaller and smaller and smaller. And as a result, if this can process continued unabated, diatoms would become minuscule. When the cell reaches a certain size it becomes fertile, and it reproduces sexually, releasing eggs and sperm and fusing into a new diatom cell, that forms a stage called an auxospore. The auxospore stage is naked, in that it does not contain a silica shell, and this auxospore stage expands and forms an initial cell, which is much larger than the fertile cell size. In this way, the vegetative cycle begins again, with the size of the diatom restored to its original level.

Species that are harmful belong to the pennate diatoms that are long and thread-like and have the ability to attach to a host, although the relationship is not symbiotic. Both dinoflagellates and diatoms cysts can move around the oceans by currents, storms, dredging of the ocean bottom, and when cysts act as ballast on ships or even higher-level organisms. Toxins are not known in the cyst stage of either group.