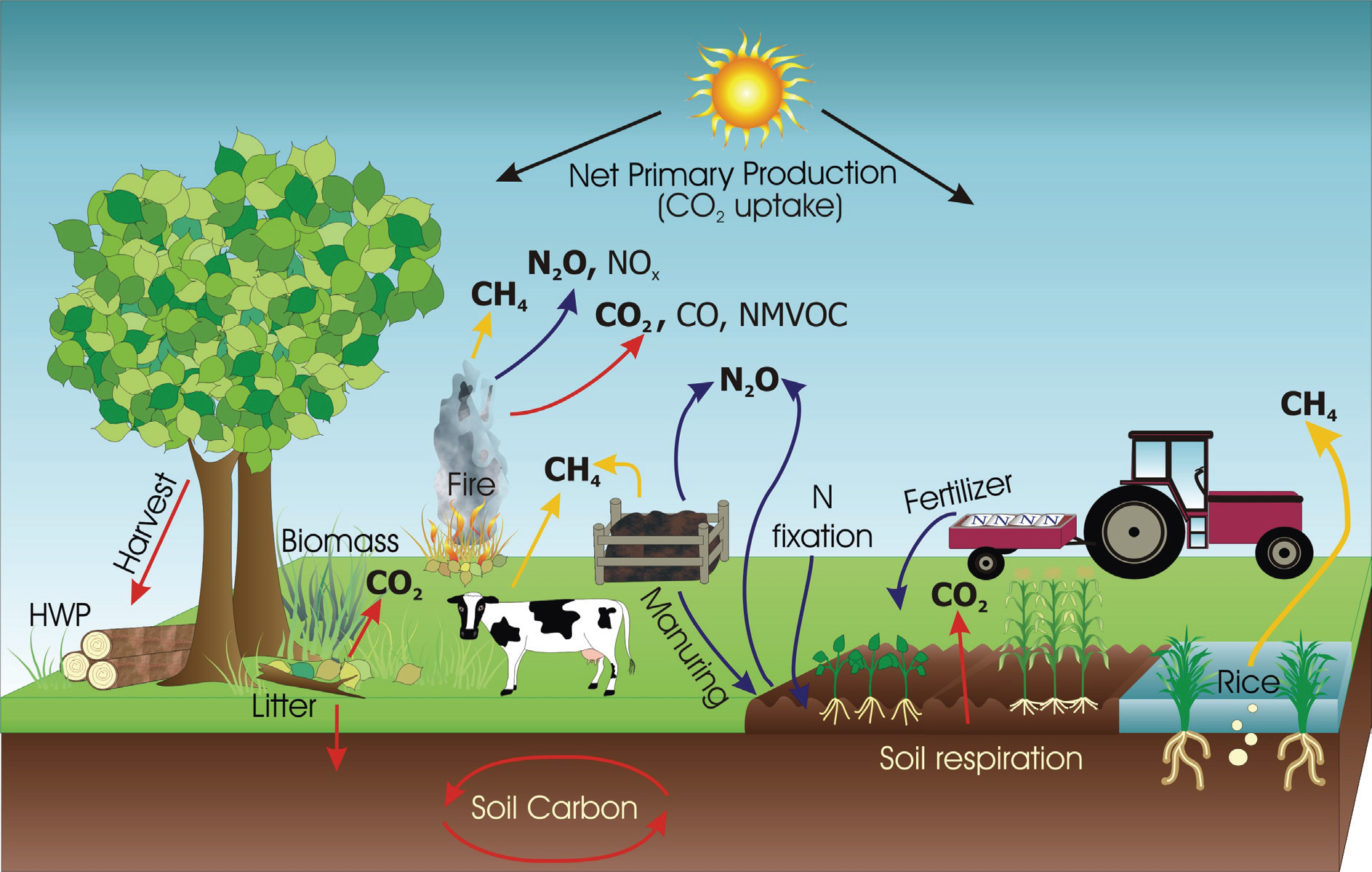

When we talk about agricultural emissions, that can mean a lot of different things as these emissions are dependent on the type of activities occurring on a farm. For our purposes for this lesson, we'll look broadly at emissions from crop production and livestock production.

It can be tricky to understand the overall role agriculture plays in global emissions because of how some of these smaller sectors are grouped together sometimes. To take a closer look, we're going to take these pieces of pie and slice them even thinner.

The graphic below demonstrates that agriculture, land use, and forestry (often called AFOLU) account for about a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions.

- Of that quarter, about half of those emissions come from agriculture (most estimates are between 9-14%).

- If we keep drilling down, of that half of the quarter of global emissions (are you still with me, hang on!), more than half come from enteric fermentation, manure management, and fertilizer use.

We'll focus our attention this week on these bigger subsector areas. And then, to keep things fun, I've included food waste in this section too. It's not technically categorized as an agricultural emissions source here, but I think in the context of our thinking about where emissions are coming from and what we can do about them, it makes sense to talk about it here (and, we're also covering waste this week - so it fits nicely with that, too).

| Source | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Electricity, heat production, and other energy | 35% |

| Industry | 21% |

| Transport | 14% |

| Buildings | 6.4% |

| Agriculture | 12% |

| Forestry and Land Use | 12% |

| Source | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Enteric Fermentation | 40% |

| Manure Left on Pasture | 16% |

| Synthetic Fertilizers | 13% |

| Paddy Rice | 10% |

| Manure Management | 7% |

| Burning of savannahs | 5% |

| Other | 9% |

In the following video, Penn State Professor (and METEO 469 course author) Michael Mann discusses the systemic changes we need - primarily in agriculture but also in other contexts of our emissions behaviors (remember proximate causes and driving forces?). He talks about the need for both individual and collective action and how those efforts work together. (This video is required course content and fair game for the content quiz/exam 1.)

Christiane Amanpour: Welcome to the program, Michael Mann.

Michael Mann: Thanks, Christiane. It’s good to be with you.

Christiane Amanpour: So, I just want to pick up a little bit from where correspondent Bill Weir left off. Because he actually showed us some very hopeful innovation and hopeful farming methods that are already taking place. Let’s just talk about how that one farmer talked about being able to plant his land, allowing it to become a constant carbon sink, and you know, to be able to really even feed vast amounts of people. Tell us what good and what’s right about those sorts of farming methods right now.

Michael Mann: Sure, so the bad news, of course, is that our farming methods: agriculture, land use, deforestation are contributing substantially to the climate crisis as this report lays bare. But, at the same time, the good news is that there is ample room for mitigation. There are things that we can do to lower those carbon emissions from the agricultural sector, from the livestock and food production. Among those, as we’ve heard, is more careful methods of planting and agriculture, no-till agriculture, growing potentially different cultivars, feeding livestock different food. Different food sources can actually lower carbon emissions, methane emissions, for example, from cows and ruminants, so there is a lot of room to decrease those carbon emissions, which collectively are a little less than 25 percent. That means that this isn’t the bulk of the problem. The bulk of the problem remains our burning of fossil fuels for energy and transportation. But this is a significant piece of the pie. We need to focus on it, and there is ample opportunity for reducing those carbon emissions in a very win-win sense. Limiting deforestation, more productive agricultural methods that will feed more people can also help us sequester carbon so it doesn’t build up so quickly in the atmosphere.

Christiane Amanpour: So then tell me because you have contributed to other IPCC reports. Tell me what the significance is, in your view, of this latest report. We know that the first one which came out warned that we had until 2030 to get our act together as a world, to meet that 1.52-degree critical temperature rise. What is this one telling us, specifically?

Michael Mann: Yes, so these interim reports, this special report, for example, on land, that occurs between the major IPCC reports like the one that was published last year are important because they focus on specific topics which are of vital importance. In this case, this report focuses on land. That’s where seven and half-billion and growing people live. It’s where we live, and climate change is already having adverse impacts on that land. It is, for example, leading to a loss of coastal land because of sea-level rise and more devastating tropical storms that are inundating our coastlines. Because of the warming of the planet, a large part of the tropics is starting to become unliveably hot. And we have seen rampant wildfires in Eurasia, in the US, that, of course, are a threat to our infrastructure. So, we have these problems, these growing problems, associated with climate change, that threaten the amount of land that we have, at a time when we have a growing global population, again, of 7 and a half billion and growing, and, as we’ve already alluded to, the warming is having an impact, for example, on our ability to raise crops and livestock, and feed that 7 and a half billion and growing people. All of these things are intertwined; all of these challenges are intertwined.

Christiane Amanpour: Can I just ask you then. Again, let’s just go back to the farmer in Iowa who talked about how you don’t really even need more retraining like maybe other sectors of the economy might. You can make these and implement these changes without a massive overhaul. But, a lot of the overhaul that is necessary, according to the report, does require a lot of government resource, and a lot of, I mean, re-education, and making an awareness-raising of how you change your habits, the use of machinery, the intensity of the farming, etc., and just the wilding that the farmer was talking about. Tell us the challenges to the overhaul of the land production and use.

Michael Mann. Yeah, this gets at the heart of the problem, which is that is that any real solution, any comprehensive solution to the climate crisis is going to have to involve both individual behavior and collective and systemic change. There are many things that individuals, that we can do in our everyday lives, including changing our dietary patterns, changing our diets, that can lower our own personal carbon footprint. And in many cases, that makes us healthier, it saves us money, it makes us feel better. So, this is low-hanging fruit. These are things that we ought to do. But, at the same time, we need incentives, governmental incentives, policies, for example, to help shift us away from our reliance on fossil fuels to renewable energy. And that can take the form of a price on carbon, or explicit subsidies for renewable energy. That’s critical, because, again, the burning of fossil fuels is more than 2/3 of the problem. But we can also have policies that help farmers and help the agricultural industry adopt practices that are more carbon-friendly, that help us draw down that carbon from the atmosphere, which is an important part of the solution, while actually increasing agricultural productivity. We can’t do that without governmental incentives that sort of point us in the right direction, that shift the collective behavior the right direction. And, how do we achieve those policies? Well, we have to make sure that we elect politicians who will vote in our interest, who will act in our interest, rather than on the part of polluting interests who too often fund their campaigns, and have them in their hip pockets.

Christiane Amanpour: So, my thought in that regard. The farmer at the very end of Bill Weir’s report was quite poignant. Because on the one hand, you know, he didn’t want to talk about the politics. He didn’t want to admit or recognize that human(s) have an involvement in climate. He’s talking about deregulation. But then he says, “But look, you know, we’re doing the right thing and it’s important that we do the right thing. It helps.” And so, he’s kind of conflicted between, what’s the right way to farm, what is the right way to look at his land, and, what are the right politics around it? So, let’s just talk, because this report does focus mostly on land, and not so much on the fossil fuels that we’ve all heard of so much already. The whole business of consumption. So, the farmers will say, “Well, ok. Fine. You tell us to plant more whole foods, more grains, plant-based food. Cut back on our cattle. Cut back on the sheep. But, what if demand doesn’t change.” And let’s just remind people what demand is about. According to IPCC, food-calories per capita has increased by 1/3. Changes in consumption patterns contribute to 2 billion overweight adults. An estimated 821 million people are still undernourished, though. 25 to 30 percent of total food produced is lost or wasted. So, there are a lot of changes that need to be made. Not just going more into plant-based and whole foods.

Michael Mann: No. That’s absolutely right and, again, gets back to the heart of the matter. There are obviously things that we can do in our everyday lives. Being less wasteful of food, and in eating food that is less harmful to the environment, that is less carbon-intensive. And shifting away from meat is an important way of doing that, if it fits, you know, within the constraints of your lifestyle. That having been said, once again, we need incentives, educational efforts, government-funded and supported outreach in the form of public service announcements and programs, to inform people about the choices they make and how they can make healthier choices. And we come up once again against some pretty entrenched interests, for example, the fast-food industry. Of course, there are other challenges when it comes to our efforts to sort of transition to healthier diets, less, again, meat -and fat-intensive diets. That’s part of the problem, but to achieve that, we need changes. We need shifts in human behavior, and those shifts won’t happen on their own. They do require coordinated efforts, through educational programs by governmental and non-governmental entities.

Christiane Amanpour: Do you - before I want to play a little clip of an interview I had with Director James Cameron and his wife Susie, and they’ve come up with a book called OMD, essentially one meal a day, and it’s about being plant-based. But before I do that, I want to ask you. Is there a comparable shift in human behavior and habits that have occurred in the past with government help and public service announcements and all the rest of it – that has worked? Because that’s what everybody says. I mean, how are we going to shift human behavior in such a dramatic way?

Michael Mann: Yeah, well, we have seen efforts of this sort succeed in the past. When it comes to global, environmental problems like ozone depletion and acid rain. Ultimately, these problems arose from practices that do occur at the individual scale. In the case of ozone depletion, it was spray cans and old leaky refrigerators — refrigerators that used chlorofluorocarbons or freons, these chemicals that ultimately get into the stratosphere and destroy it. So it was individual behavior that was putting those chemicals into the atmosphere. And yet, what we saw was that a market-oriented program to place incentives that move the industry away from using those ozone-depleting chemicals ultimately did lead to the solution of the problem. We’ve seen massive recovery now of the ozone hole around Antarctica, because of those systemic changes that ultimately simply provided better choices to individuals and consumers, choices that don’t damage the planet.

Christiane Amanpour: I think that is really an optimistic and important reminder, that actually these things can work and can work in a way that is not just beneficial to the planet, but beneficial to individuals as well. It doesn’t cost them much. Here is what, though, on the planet and food and land issue that we are talking about particularly with this report, Director James Cameron and his wife told me a while ago.

Susie Cameron: What you’re putting on your plate actually makes a huge difference, towards not only climate change, but your health as well.

Director James Cameron: Um-hmm!

Interviewer: And, I guess….

Director James Cameron: And, the health of the planet. I …

Interviewer: Yeah. Go ahead…

Director James Cameron: Just the health of the planet. I mean, the quickest and easiest way for an individual to be, to feel empowered and to make a difference and to be able to look at their face in the mirror in the morning, and think: I’m making a difference, I’m doing something positive, not just for myself, my own health and my family’s health, but for the health of the planet, is to change how we eat.

Christiane Amanpour: So again, how does one shift populations? But you sort of indicated. Interestingly, in the report that we heard from Bill Weir, the farmers say, that the harsher the climate gets, the worse it is for them and for their land, and for their ability to make it economically. So, just wondering. We’ve had the hottest July on record here in Europe. You’ve got wildfires, a massive, massive amount, in Siberia. Even President Putin is talking about having to direct the state towards figuring out what to do. But of course, their economy kind of depends on fossil fuels. And so, I guess, how long do you think we have? And how? … You know, the ship of state, it says, is so difficult to turn around. How much effort and time is it going to take to just deal with the land issue?

Michael Mann: Yeah, and it’s important to realize that while there are economies that still rely on fossil fuels, the health of the planet relies on us getting off fossil fuels. And that’s of course, of far greater importance. We won’t have an economy to talk about if we don’t have a livable planet. So, you know, James Cameron makes some important points here. There is agency. There are things we can do in our everyday lives that do help solve this problem. And, by the way, they put us on a path. As we engage in these actions, we become more invested in solving this problem and more likely to participate in collective efforts, putting pressure on policy-makers, doing all those other things we can do to make sure that there is the systemic change that we need, that moves us away from fossil fuels, that moves us away from a carbon-intensive food system. There are all of these things we can do in our everyday lives, and changing your diet is one of the simplest things to do. I have chosen to not eat meat for a number of reasons, and I feel good about that choice. I feel healthier for having made that choice. But I don’t want to mandate other people’s choices. What I want to do is to provide them with the information necessary for them to make informed choices about their own individual actions, and more importantly to get them on that path of engagement, where they participate in the broader, collective action necessary for this dramatic systemic change that we need. By the way, as you allude to, over really just a decade, we need to bring those carbon emissions down by a factor of 50% and then down to near zero – 50% by 2030 and near 0 by 2050 if we are to avert the most catastrophic impacts of climate change.

Christiane Amanpour: OK

Michael Mann: But the good news there: the preliminary numbers are in for 2019. Obviously, 2019 isn’t finished yet, and there are lots of things that can happen. But based on the preliminary numbers, we’re seeing a significant drop of more than a percent in carbon emissions this year.

Christiane Amanpour: Wow!

Michael Mann: Another hint that maybe we’re starting to bend that curve downward, and we need to bend it down rapidly. But the first step is to bring those emissions to a plateau and start that decline…

Christiane Amanpour: That’s great!

Michael Mann: …towards 2030 and 2050 where we need to be.

Christiane Amanpour: That is very, very good news. And particularly what you say, Individuals can make a difference. And we’re obviously seeing it amongst young people, who put this issue of climate and environment at the very top of their political agenda. Michael Mann. Thank you very much indeed.