The livestock we raise for meat and dairy consumption has a sizable impact on the global emissions profile.

Sometimes, the popular media likes to capitalize on the sensational nature of talking about cow burps and farts and greenhouse gas emissions (see Forbes article for proof). And maybe this isn't all bad if it gets people talking (and possibly giggling) about the role our diet plays in the global climate crisis. (Did the instructor really use the word 'farts' in class? I think so...). And while that's certainly part of the puzzle, livestock-related emissions are much more complex and varied. We're going to take a look at several broad categories (as outlined by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations).

| Type | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Enteric, CH4 | 39.1 |

| Applied & Deposited manure, N2O | 16.4 |

| Feed, CO2 | 13.0 |

| Fertilizer & Crop Residues, N2O | 7.7 |

| LUC: pasture expansion, CO2 | 6.0 |

| Manure Management, N2O | 5.2 |

| Manure management, CH4 | 4.3 |

| LUC: soybean, CO2 | 3.2 |

| Postfarm CO2 | 2.9 |

| Direct Energy, CO2 | 1.5 |

| Feed: rice, CH4 | 0.4 |

| Indirect Energy CO2 | 0.3 |

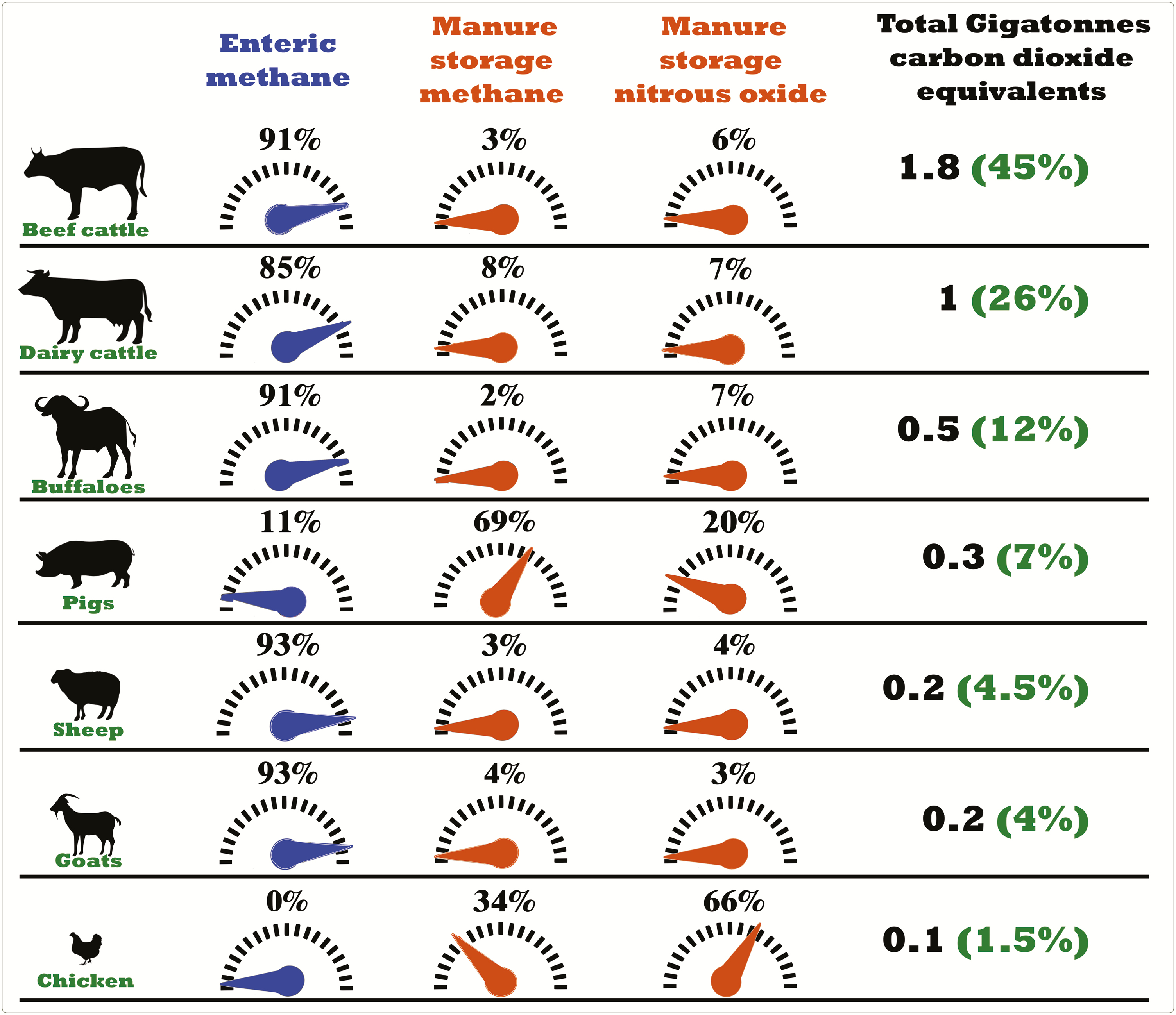

The emissions profile for livestock production varies by species. For example, if you look at this graphic below, you'll notice that almost all of the emissions associated with beef production come from enteric fermentation (the often satirized burps and farts, if you will), while chickens - not ruminant animals like cows - have no emissions from enteric fermentation and instead, their emissions are coming exclusively from manure management.

| Animal | Enteric Methane | Manure Storage Methane | Manure Storage Nitrous Oxide | Total Gigatonnes cO2 equivalents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beef Cattle | 91% | 3% | 6% | 1.8 (45%) |

| Dairy Cattle | 85% | 8% | 7% | 1 (26%) |

| Buffalos | 91% | 2% | 7% | .5 (12%) |

| Pigs | 11% | 69% | 20% | 0.3 (7%) |

| Sheeps | 93% | 3% | 4% | 0.2 (4.5%) |

| Goats | 93% | 4% | 3% | 0.2 (4%) |

| Chickens | 0% | 34% | 66% | 0.1 (1.5%) |

Before returning to Penn State to teach in the ESP Program, I worked as a Policy Analyst and Account Manager for a greenhouse gas offset project developer called Environmental Credit Corp. (now ClimeCo). Most of the offset projects we developed were related to manure management on hog and dairy farms. So, while all this chatter about manure this week may seem a bit unconventional or even gross to you, I guess I'm just used to knowing more about animal poop than I ever imagined I might! I thought I'd share a little bit of that experience with you here, as it relates to reducing greenhouse gas emissions from manure management practices on large-scale farming operations.

Many dairy and hog farmers use 'manure lagoons' for long-term storage of their manure. To put this bluntly, if you have a thousand (or in many cases way more than a thousand) anythings going to the bathroom every day, you need to figure out where all of that waste is going to go. For many farmers, manure lagoons offer a cost-effective and logical solution. They pump the manure into lagoons (they look like ponds, only you don't want to swim there!) and then several times a year, draw the manure out and land apply it to their fields as fertilizer. But, for the time, it's just sitting there, the manure is decomposing aerobically (with oxygen) and releasing methane directly into the atmosphere (and stinking up the neighborhood). The company I worked for partnered with USDA to offer farmers a simple alternative - covers for their manure lagoons. In the most simplistic of terms, we put tarps over these big ponds to capture the gas. In reality, it's a bit more complicated than that, and under those tarps (which are really 60 mm thick high density plastic), is a series of pipes to collect the gas. Now, the manure is decomposing anaerobically (because we took away the oxygen) and we can capture that gas.

What would we do with a bunch of captured methane? Well, there are a few options. The first, and less ideal option is simply to flare it. When it combusts, it combusts as carbon dioxide. So, there's still a greenhouse gas emission which occurs, but remember, its global warming potential is so much less than methane, there is a benefit to this. But it seems wasteful to just flare it when we can use it.

I'd like you to 'meet' Tom Butler. Tom was one of my favorite clients. He's a hog farmer in Lillington, NC and runs an 8,000 head feeder to finish operation. We covered Tom's manure lagoons in 2006 or thereabouts. Initially, we just flared the gas. But over the years, Tom has built a renewable energy empire on that hog farm, and he's now using all of his gas on-site to power his farm. How neat is that? And, lagoon covers offer some ancillary benefits worth noting, too. Think about Hurricane Dorian - do you want a hurricane's worth of rain dumping into a manure lagoon and possibly causing it to run over? No, you do not. With a covered lagoon, Tom doesn't have to worry about (increasingly more frequent) extreme weather events. Also, covered lagoons drastically reduce odor issues. I'll admit, I was nervous the first time I pulled up to Tom's farm. My husband had lived in North Carolina and assured me there was no smell quite like a hog farm. But, it actually was pretty tolerable.

Tom's a great example of a progressive farmer who is trying his best to do right by land, his animals, and the planet, and I thought it'd be nice to share this story with you, even if it is mostly about manure.

I couldn't dig up the picture, but I have a picture of me standing out on this lagoon. It's like standing on a water bed, only that's not water underneath the cover. Joking aside, Tom's crew and ours had to manage the cover very carefully - methane is highly combustible (obviously) and dangerous to work around. The life expectancy on a cover like this is 20-30 years, so Tom's still has a fair bit of life in it, and I'm excited to see what he'll do next. For perspective, this lagoon is over an acre in size.