Prioritize...

You should be able to apply your knowledge of energy transfer (particularly via radiation and convection) to explain why clouds do not act like blankets to keep nights warmer.

Read...

You now know that all else being equal, a clear, calm night will be colder than a cloudy and/or windy night. That's because clear, calm nights maximize the earth's surface radiation deficit, paving the way for nocturnal inversions to develop as conduction dominates. But, either wind or the presence of cloud cover can limit nocturnal chill near the ground. We just covered at length how wind can limit nocturnal chill (by mixing from mechanical eddies). But, with your knowledge of radiation, we can debunk what is easily the most popular explanation for why clouds keep nighttime temperatures higher:

Motivating Myth: Clouds act like blankets to keep nights warmer.

Likening clouds to blankets to explain their role in keeping nighttime temperatures higher near the surface of the earth is very common, and you've likely heard that "clouds act like blankets" if you took a weather course at some point in your previous education, or you ever heard a meteorologist try to explain the phenomenon quickly on a TV weathercast. "Clouds act like blankets" gets repeated so frequently because it's a simple analogy, but it's also very wrong. Yes, both clouds and blankets keep things warmer, but that's where the similarities end, and with our knowledge of radiation and convection, we can cast the idea of clouds acting like blankets onto the scientific scrap heap.

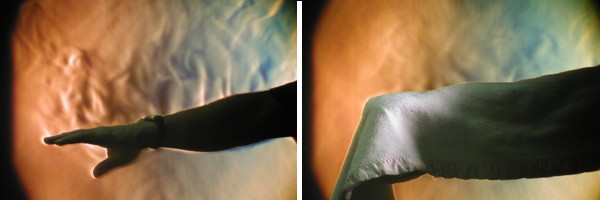

For starters, have you ever thought about how a blanket keeps you warm? If you haven't, the Schlieren photography that I introduced in the last section provides the answer. Check out the side by side images below. On the left is a Schlieren photograph of former meteorology instructor Lee Grenci's bare arm. On the right is a Schlieren photograph of Lee's arm covered with a (relatively porous) cotton blanket.

Notice how the blanket greatly reduces the escape of convective thermals away from Lee's skin. You can still see some convective thermals escaping even from Lee's blanketed arm because the cotton blanket is so porous, but there's still obviously a significant reduction compared to Lee's bare arm. So, now do you know how blankets keep you warm? Blankets suppress convection away from your skin, which reduces the transfer of heat energy away from your body.

For a blanket to be effective, it must be close to your body so that it can keep the warm air right next to your skin, and prevent it from rising away and mixing with colder air in the room. Think about it: would a blanket keep you warm if it was suspended above you like a tent with no sides? Of course not! You could verify this by nailing a blanket to your bedroom ceiling and seeing if it makes you feel warmer, but I wouldn't recommend it. The result is intuitive: A blanket fastened to your ceiling will not warm you up. Yet, we're asked to believe that clouds located hundreds or thousands of feet above the earth's surface keep nights warmer because they "act like blankets." Nonsense!

Clouds have no ability to suppress convection or trap warm air near Earth's surface. Furthermore, at night, there's typically no free convection to suppress anyway. So, clouds can't act like blankets. They are simply sources of downwelling IR radiation that is absorbed by the earth's surface, reducing (or sometimes completely eliminating) the ground's typical nighttime radiation deficit, which helps keep surface temperature higher than it would be on a clear night.

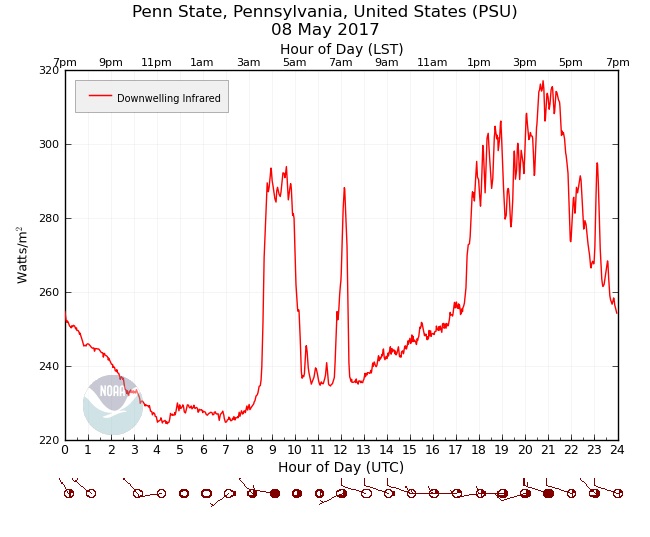

To seal the deal, check out the plot of downwelling IR from Penn State University on May 8, 2017 below. Toward the bottom of the image, I've included the corresponding sky coverage as reported on the local station model. Note the big spike up in downwelling IR after 08Z (from about 225 Watts per square meter to about 290 Watts per square meter), which corresponded to an increase in cloud cover. After 10Z, downwelling IR dipped again, and we can see from the station models that between 10Z and 11Z, the cloud coverage went from "broken" (mostly cloudy), to scattered (partly cloudy), so fewer clouds meant a reduction in downwelling IR.

The trends from the graph are unmistakable: every time cloud coverage increased, downelling IR increased, too, and when cloud coverage was reduced, downelling IR displayed a corresponding decrease. So, the take-home message here is that clouds act like space heaters because clouds serve as additional sources of radiation (downwelling IR) for the earth's surface. Clouds don't suppress convection like blankets do, so clouds do not "act like blankets" in keeping nights warmer. Of course, blankets emit some radiation, too (all things emit radiation at all wavelengths at all times), but no more than any other household object. Radiation emitted by a regular blanket is not enough to make you feel warmer.

Now, whenever you hear someone say that "clouds act like blankets," you know better, and you can avoid believing such "junk science!"