Human Health

There are a variety of human health concerns associated with warming in the future. The most serious concern is related to deaths caused by heat waves.

As discussed in Module 2, late June 2021 saw record-breaking heat in the Pacific Northwest of the US and Canada, with Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver shattering previous temperature records. Temperatures reached 116 degrees C in Portland, 108 degrees C in Seattle, and 121 degrees C in Lytton in British Columbia. The heatwave resulted from a massive heat dome that developed and sat over the area. This dome of hot air was very dry and led to wildfires.

This area was truly vulnerable to heat as only about 40% of homes have air conditioning and residents are not used to extreme heat. Thus, estimates are that over 500 people died as a result of the heat, many of whom in vulnerable populations, older and poorer people.

Climate models show that this region will need to become accustomed to the heat, and these severe temperatures will occur regularly as the 21st century progresses. In fact, temperature data clearly show warming in this region over the last century.

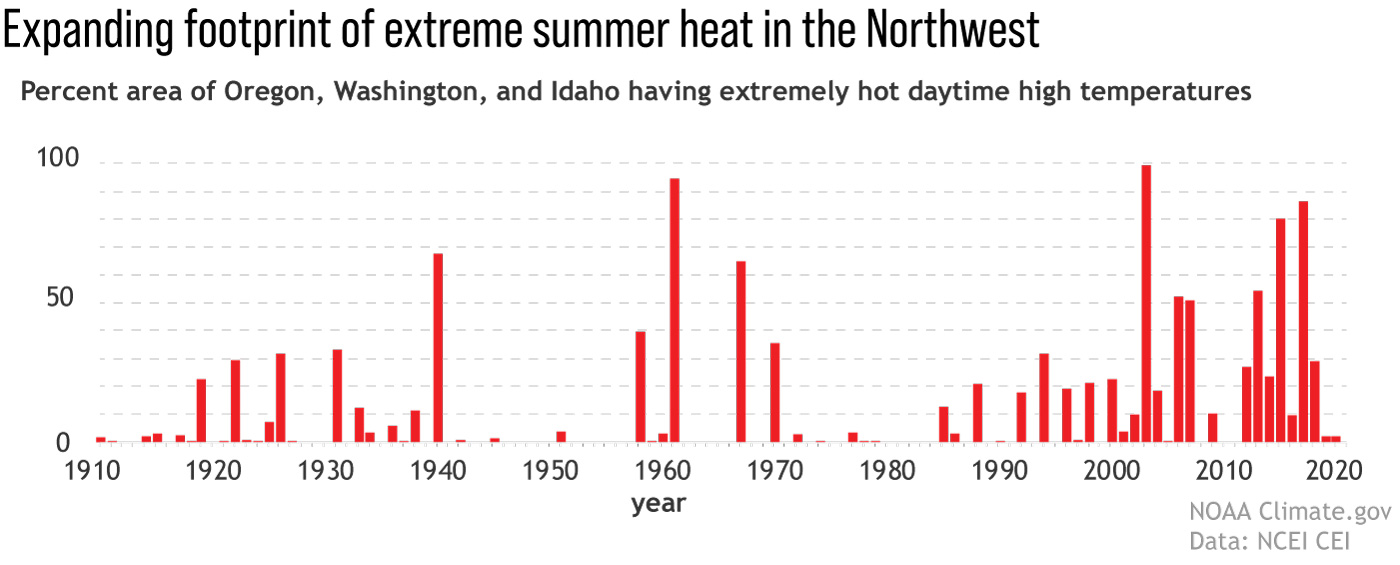

The graph shows the percent area of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho experiencing extremely hot daytime high temperatures from 1910 to 2020. The y-axis represents the percentage (0 to 100%), and the x-axis shows years in decades. The graph indicates a general increase in the affected area over time, with notable peaks around the 1930s, 1960s, and 2010s, where the percentage reaches or exceeds 80%, while earlier decades show minimal impact, mostly below 20%.

- Graph Overview

- Title: Expanding footprint of extreme summer heat in the Northwest

- Subtitle: Percent area of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho having extremely hot daytime high temperatures

- Source: NOAA Climate.gov, Data: NCEI CEI

- Type: Bar graph

- Time Period: 1910 to 2020

- Axes

- Y-axis: Percentage (0 to 100%)

- X-axis: Year (1910 to 2020, by decade)

- Trend

- Early 20th Century (1910-1940): Minimal impact, mostly below 20%

- Mid-20th Century (1940-1970): Peaks around 80% in the 1930s and 1960s

- Late 20th to Early 21st Century (1980-2020): Significant increases, with peaks exceeding 80% in the 2010s

- Visual

- Bars: Red, height representing percentage affected

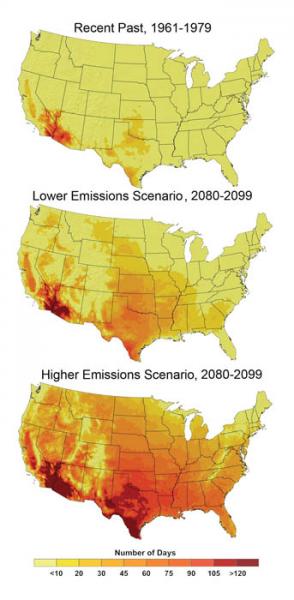

In the US as a whole, the future almost certainly will have more frequent hot days and nights. This can be seen in the following set of maps, which show the number of days over 100°F for the recent past and the end of this century under two different emissions scenarios:

The message here is that throughout most of the country, we will be challenged with many more hot summer days. By the end of the century, a cool, northern state like Minnesota will have more +100°F days than the southern tip of Texas. What can be done about this? How can we adapt? Can we mitigate the impacts of these extreme heat events?

Some excellent examples of how to adapt to and mitigate the consequences of these extreme heat events come from several US cities. Philadelphia, in 1995, launched a Hot Weather Health Watch and Warning System to respond to health threats from more frequent heat waves. The system includes education, media alerts, information hotlines (no pun intended), and cooling shelters. They estimate that this system has already averted more than 100 heat-related deaths. Both New York City and Chicago have taken steps to cool their downtown areas by covering roofs with reflective materials and plants; these steps will mitigate the overheating in the city centers, where temperatures can be as much as 4°C warmer than the surroundings. In addition to minimizing heat-related deaths, these measures will also reduce the amount of electricity needed for cooling, thus providing an extra benefit. Many regions are modifying building codes to promote new buildings that are easier to keep cool (and easier to keep warm).

So, there are some relatively easy measures that can be taken to adapt to more frequent heat waves.

As the climate warms, many areas are already finding that new infectious diseases are becoming a problem. One familiar example of this is West Nile Disease, a disease spread by a species of mosquito that is normally found in warm regions of the world. This disease, once introduced to the US, has spread rapidly, aided by generally warmer temperatures. There have been more than 30,000 cases of West Nile Disease in the US and over 1,000 deaths. In the US, we are already adapting to this new disease through education and the use of pesticides to limit the spread of the mosquitoes. Similar new diseases can also be adapted to, but public health officials will have to be diligent in looking out for the arrival of the new diseases — which is something they already do.

In summary, although warming will bring new challenges to human health, the adaptations are relatively straightforward, and in many places, they are already beginning.