Feedback Mechanisms

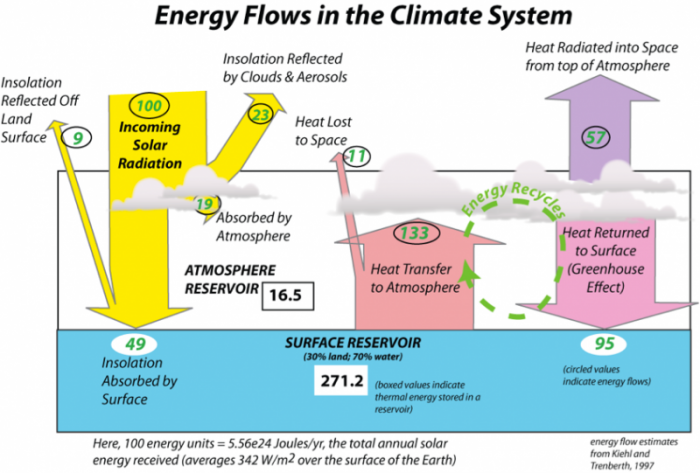

The image is a diagram titled "Energy Flows in the Climate System," illustrating the flow of solar energy through Earth's climate system, including the atmosphere and surface reservoirs. It quantifies the energy in units (relative to 100 units of incoming solar radiation) and highlights processes like reflection, absorption, heat transfer, and the greenhouse effect. The diagram is attributed to Kiehl and Trenberth (1997).

- Overall Structure:

- The diagram is divided into three main sections: incoming solar radiation (left), the atmosphere (center), and the surface reservoir (bottom). Arrows and numerical values indicate the flow and distribution of energy.

- Incoming Solar Radiation (Left Side):

- 100 units: Represented as a yellow arrow labeled "Incoming Solar Radiation," entering from the top left.

- 9 units: Reflected off the land surface, labeled "Insolation Reflected off Land Surface" (yellow arrow pointing back upward).

- 23 units: Reflected by clouds and aerosols, labeled "Insolation Reflected by Clouds & Aerosols" (yellow arrow pointing upward).

- Total Reflected: 9 + 23 = 32 units of the incoming 100 units are reflected back to space.

- Atmosphere (Center Section):

- 19 units: Absorbed by the atmosphere, labeled "Absorbed by Atmosphere" (yellow arrow curving into the atmosphere).

- 16.5 units: Labeled "Atmosphere Reservoir," indicating the energy stored in the atmosphere.

- 11 units: Lost to space as heat, labeled "Heat Lost to Space" (purple arrow pointing upward).

- 133 units: Transferred from the surface to the atmosphere, labeled "Heat Transfer to Atmosphere" (red arrow pointing upward).

- 57 units: Radiated into space from the top of the atmosphere, labeled "Heat Radiated into Space from top Atmosphere" (purple arrow pointing upward).

- 95 units: Returned to the surface via the greenhouse effect, labeled "Heat Returned to Surface (Greenhouse Effect)" (green arrow pointing downward).

- A section labeled "Energy Recycles" indicates the cycling of energy between the surface and atmosphere.

- Surface Reservoir (Bottom Section):

- 49 units: Absorbed by the surface, labeled "Insolation Absorbed by Surface" (yellow arrow pointing downward).

- 271.2 units: Labeled "Surface Reservoir (30% land; 70% water)," indicating the total energy at the surface.

- A note within the surface reservoir states: "(boxed values indicate thermal energy stored in a reservoir)," referring to the 271.2 units.

- Another note states: "(circled values indicate energy flows)," referring to the other numerical values in the diagram.

- Energy Balance Note (Bottom Left):

- A note at the bottom left reads: "Here, 100 energy units = ~5.56E24 Joules/yr; the total annual solar energy received (averages ~342 W/m² over the surface of the Earth)," providing the scale for the energy units used in the diagram.

- Visual Elements:

- The diagram uses color-coded arrows to represent different energy flows:

- Yellow for incoming and reflected solar radiation.

- Red for heat transfer from the surface to the atmosphere.

- Purple for heat lost to space.

- Green for heat returned to the surface via the greenhouse effect.

- Clouds are depicted in the atmosphere, and the surface is divided into land (30%) and water (70%).

- The diagram uses color-coded arrows to represent different energy flows:

The diagram effectively illustrates the energy balance of Earth's climate system, showing how incoming solar radiation is distributed, reflected, absorbed, and re-radiated, with a significant portion recycled through the greenhouse effect, as quantified by Kiehl and Trenberth in 1997.

The view of the climate system depicted in the adjacent figure is one of stability — energy flows in and out, in perfect balance, so the temperature of the earth should stay the same. But if we can learn anything from studying Earth’s history, we learn that change is the rule and stability the exception. When change occurs, it almost always brings feedback mechanisms into play — they can accentuate and dampen change, and they are incredibly important to our climate system. There are many good examples of feedback mechanisms, but here are a few to illustrate the idea.

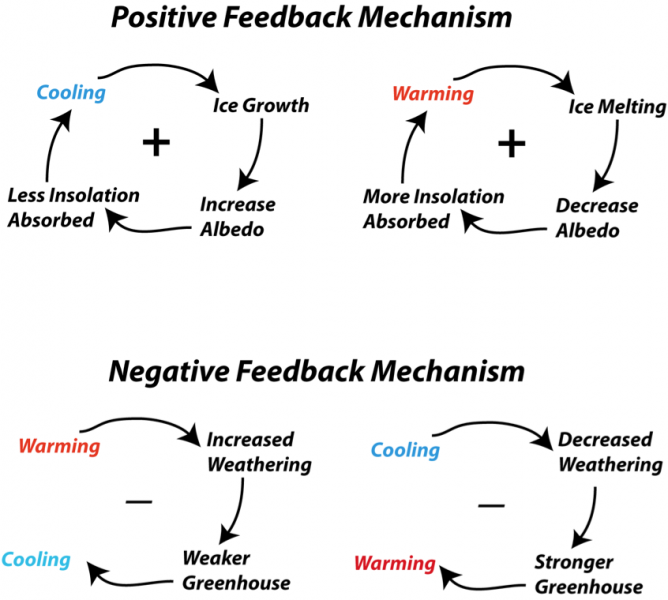

Ice — Albedo Feedback

Ice reflects sunlight better than almost any other material on Earth, and in reflecting sunlight, it lowers the amount of insolation absorbed by Earth, which makes it colder. If the Earth becomes colder, more ice may grow, covering more area and thus reflecting even more insolation, which in turn cools the Earth further. Thus cooling instigates ice expansion, which promotes additional cooling, and so on — this is clearly a cycle that feeds back on itself to encourage the initial change. Since this chain of events furthers the initial change that triggered the whole thing, it is called a positive feedback (but note that the change may not be good from our perspective). Positive feedback mechanisms tend to lead to runaway change — some small initial change is thus accentuated into a major change.

Weathering Feedback

Rocks exposed at the surface interact with water and the atmosphere and undergo a set of chemical and physical changes we call weathering. The chemical part of weathering often involves the consumption of carbonic acid (formed from water and carbon dioxide) in dissolving minerals in rocks. This process of weathering is thus a sink for atmospheric carbon dioxide, which is an important greenhouse gas. If you remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, you weaken the greenhouse effect and this leads to cooling of the Earth. Like many chemical reactions, this chemical weathering occurs more rapidly in hotter climates, which are associated with higher levels of carbon dioxide. So consider a scenario in which some warming occurs; this will encourage faster weathering, which will consume carbon dioxide, which will lead to cooling. In this case, the initial change triggered a set of processes that countered the initial change — this is called a negative feedback (even though it may have beneficial results) because it works in opposition to the change that triggered it.

Cloud Feedback

Another important negative feedback mechanism involves the formation of clouds. On the whole, clouds in today's climate have a slight net cooling effect — this is the balance of the increased albedo due to low clouds and the increased greenhouse effect caused by high cirrus clouds. As a general rule, as the atmosphere gets warmer, it can hold more water vapor, and with more water vapor, we expect more clouds, and the increased clouds will then tend to limit the warming that initiated the increased clouds — thus we have another negative feedback mechanism.

Positive and Negative Feedbacks — Yin and Yang

In Asian philosophy, yin and yang can be thought of as interacting, interconnected forces that are essential components of a dynamic system. In the Earth system, positive and negative feedbacks are a bit like yin and yang — they are essential components of the whole system that ultimately play an important role in maintaining a more or less stable state. Positive feedback mechanisms enhance or amplify some initial change, while negative feedback mechanisms stabilize a system and prevent it from getting into extreme states. In many respects, the history of Earth’s climate system can be seen as a bit of a battle between these two types of feedback, but in the end, the negative feedbacks win out and our climate is generally stable with a limited range of change (excepting, of course, a few extremes such as the Snowball Earth events back around 750 Myr ago).

The image consists of two sets of diagrams illustrating feedback mechanisms in the climate system, specifically focusing on positive and negative feedback loops. The diagrams use arrows and labels to show the relationships between different climate variables.

- Top Section: Positive Feedback Mechanism

- Left Diagram (Cooling Cycle):

- Components and Flow:

- "Cooling" (in blue) leads to "Ice Growth" (with a "+" sign indicating a positive relationship).

- "Ice Growth" leads to "Increase Albedo" (more ice reflects more sunlight).

- "Increase Albedo" leads to "Less Insolation Absorbed" (less solar energy absorbed due to higher reflectivity).

- "Less Insolation Absorbed" loops back to "Cooling," completing the cycle.

- Description: This cycle shows that cooling promotes ice growth, which increases albedo (reflectivity), reducing the absorption of solar energy and further enhancing cooling—a self-reinforcing loop.

- Components and Flow:

- Right Diagram (Warming Cycle):

- Components and Flow:

- "Warming" (in red) leads to "Ice Melting" (with a "+" sign indicating a positive relationship).

- "Ice Melting" leads to "Decrease Albedo" (less ice means less reflectivity).

- "Decrease Albedo" leads to "More Insolation Absorbed" (more solar energy absorbed due to lower reflectivity).

- "More Insolation Absorbed" loops back to "Warming," completing the cycle.

- Description: This cycle shows that warming causes ice to melt, decreasing albedo, which increases the absorption of solar energy and further enhances warming—another self-reinforcing loop.

- Components and Flow:

- Left Diagram (Cooling Cycle):

- Bottom Section: Negative Feedback Mechanism

- Title: "Negative Feedback Mechanism" is written below the positive feedback section.

- Left Diagram (Warming to Cooling):

- Components and Flow:

- "Warming" (in red) leads to "Increased Weathering" (with a "−" sign indicating a negative relationship).

- "Increased Weathering" leads to "Weaker Greenhouse" (weathering removes CO2 from the atmosphere, reducing the greenhouse effect).

- "Weaker Greenhouse" leads to "Cooling" (in blue).

- "Cooling" loops back to "Warming," completing the cycle.

- Description: This cycle shows that warming increases weathering, which weakens the greenhouse effect by removing CO2, leading to cooling—a self-regulating loop that counteracts the initial warming.

- Components and Flow:

- Right Diagram (Cooling to Warming):

- Components and Flow:

- "Cooling" (in blue) leads to "Decreased Weathering" (with a "−" sign indicating a negative relationship).

- "Decreased Weathering" leads to "Stronger Greenhouse" (less CO2 removal allows the greenhouse effect to strengthen).

- "Stronger Greenhouse" leads to "Warming" (in red).

- "Warming" loops back to "Cooling," completing the cycle.

- Description: This cycle shows that cooling reduces weathering, allowing CO2 to accumulate and strengthen the greenhouse effect, leading to warming—a self-regulating loop that counteracts the initial cooling.

- Components and Flow:

- Visual Elements:

- Arrows indicate the direction of influence between variables.

- "+" signs in the positive feedback diagrams indicate that the variables reinforce each other.

- "−" signs in the negative feedback diagrams indicate that the variables counteract each other.

- "Cooling" is written in blue, and "Warming" is written in red to differentiate the temperature changes.

The diagrams effectively illustrate how positive feedback mechanisms (like the ice-albedo feedback) amplify climate changes, while negative feedback mechanisms (like the weathering-greenhouse feedback) act to stabilize the climate system by counteracting changes.