Hurricanes

Like many Americans, I used to dream of owning coastal property. I have experienced hurricanes - I went to help friends recover from Andrew in Miami in 1992, and I lived through Hurricane Fran in NC in 1996, so I’ve seen the destruction they can cause. But I still maintained my dream. Every time I go to the beach, I pick up real estate brochures; on a cold, snowy weekend, I would look at coastal properties on Zillow. But my dream is being replaced by practicality. Coastal property is a risky investment in the 21st century! The research shows that fueled by increased heat from global warming, hurricanes are becoming stronger, slower moving and wetter, all recipes for increased devastation of coastal communities.

We are going to focus on storms from 2017, 2019, and 2020. We start by looking at the year 2017. Harvey, Irma, Maria, three massive hurricanes occurred in three weeks! The big question is whether 2017 was just an unusually active year, or if these monster storms are a new normal, the grand result of a warming planet.

Hurricane Harvey, August 2017

Each of these storms had some incredible elements. The eye of Harvey roared ashore in south Texas more than a hundred miles south of the booming metropolis of Houston, the fourth-largest city in the US with a population of close to 6 million people. The storm moved north towards the city and literally parked there for 4 or 5 days drawing moisture in from the warm Gulf of Mexico. By the time the storm moved on to the north, parts of Houston had received close to 52 inches of rain. Harvey dumped a grand total of 33 trillion gallons of water on Houston and points north, causing catastrophic flooding. Just for context, 33 trillion gallons would fill a cube with sides of 3 miles, it’s a massive amount of water! Several small creeks north of the city were over 19 feet over their banks. The storm was the single largest rain event in the lower 48 states of the US ever! The total damage, still rising as I write this, is estimated to be about $150 billion, again one of the largest ever catastrophes. Harvey caused 82 deaths in the US.

At the outset, Houston is a very flood-prone city. Houston lies on a flat plain near the ocean. The natural landscape is grassland that is drained by creeks called bayou. The city lies very close to the Gulf of Mexico, which gets very warm in the late summer, close to 87 degrees F! This warmth is transferred to the air keeping coastal areas warm and humid. The Gulf is an enormous heat and water factory. A key fact to understand is that for every one degree of temperature increase, an air mass can hold 3 % more moisture, so as the Gulf has warmed over recent years it contributes more energy and rain to hurricanes making them most intense and much wetter.

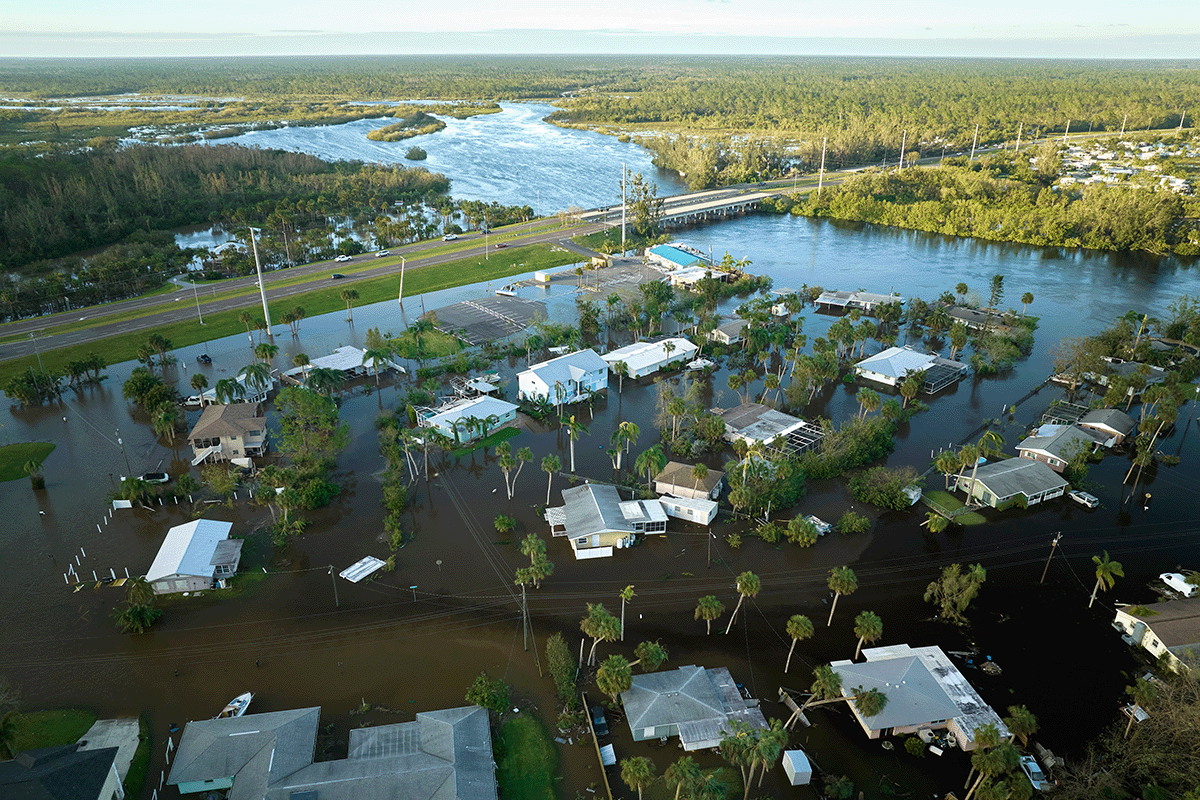

Houston might have been able to absorb this change in its natural state, but the city has grown very rapidly over the last two decades as industry has surged and jobs have been plentiful. The city prides itself on being business-friendly and as a result, it has no zoning, meaning that there are few limits on construction. A shopping mall or factory can be located right next to a housing development or a city park. As a result, the city has a massive amount of concrete, roads, parking lots, and rooftops with very little consideration paid to drainage. This contributed in a major way to flooding during Harvey as the photographs below testify. Harvey was a 1000-year event, meaning the levels of rainfall are only expected that rarely. But as it turns out, the storm was the third 500-year event in the last three years. So, it is clear that it is part of a new normal. After Harvey the city has started to make minor changes to the way it is developing requiring new homes in the floodplain to be built higher, but it still is resisting zoning measures that would keep homes out of flood-prone areas.

Video: When the roads turned to rivers: Texas in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey (11:38)

GLORIA ANDERS: It start thundering. And the lights like kind of flickered. Then the rain came. It was fine. It stopped. Saturday, the rain came. It start thundering and the lights, the lights went off.

MELVIN WOOLRIDGE: Forty-two years been living in Houston Texas, this is the worst that we have ever had on record. You know, whole city's under water.

TILFORD CURTIS: It was wild. It was like, I would think I wouldn't believe it till I seen it. When I seen all that water, you know what I'm saying. Oh sure. So you know the water was up here to me in my home. My neighbor was taller than me. So the water was up to his chest. So I had to tiptoe. I know, I know it flood out there, but when I seen it for myself and I had to get in the water, oh man, I was terrified. I was like, oh man they got snakes and stuff out there.

MARVA DANIELS: I really got frightened when the water came inside the house. And the water came all the way up to my knees.

GREG WHITE: I live right there. He just comes by and asks you if you need help.

HOWARD HARRIS: I live right there and the last time we flooded like this I went and bought this jon boat. And I'm like, if it ever happens again I'm going to have a boat here. If anybody needs anything I'll help them the best I can. I want everybody to be safe and be able to get out of the neighborhood and stuff, you know.

MAN: Don't wait on the help. We are the help.

WOMAN: Coordinate. Maybe one team go with these boats one team go with these boats. And another team go with these boats. That way we know medical training is in that area.

JOHN MCQUEEN: This is a chance for us to do some good. We will certainly give it a shot.

BEN THERIOT: We're heading over to try to head as far west as we can see if we can help people out. Man I flooded last year in 2016 in August and people came and helped me and it's a chance for me to give back.

BRYAN RAUBEND: You know we'll never forget, you know, when they came to our rescue basically. So we just want to help out in any way we can.

ANDRE MCDANIEL: I was able to take some time away from home. I've got an able body and some hands and my cousin's got a boat, and there's a lot of people that need help right now.

DYLAN GAUDET: We're going to help out as much as we can. We was in the flood last year. We know how it feels. So we're gonna give, help out as much as we can.

TIM ISOM: And it looks like we're headed towards a subdivision. There's an area where the roads are washed out. They're saying that they need some help.

WOMAN: You're in a situation like this, and myself, I can't swim. And when you're in a situation like this and you don't know what to do or where to run, that's hard. And some people you know, when they tell you to evacuate, do it.

MAN: Normally I'm fixing these things not riding in the bucket of it.

WOMAN: We just wanted to get out. It was just too much. No water. No lights. And we know that there's going to be another rainstorm coming in.

MAN: Hello.

MAN: We're going to come back by here in just a minute okay?

WOMAN:Just being there, seeing all of this and not being able to do anything, for anybody.

JENNIFER WADYKA: We're just helping people. These streets that are flooded. And we thought we saw a couple of people down here in boats. They looked like they need help. So we decided to come out here and help them. I've never seen nothing like this in my life. I wasn't here for any of the hurricanes or nothing like that. So this is craziness. A lot of sadness.

GABE VAUGHN: We just look for people on their porch waving. Or you try to find somebody who maybe who has help written on their door. Maybe a white towel hanging or something like that so that they can signal somebody that they need some help. Everybody wants to stay till it gets dark. And when it gets dark everybody wants to get out.

LEE WHEELER: I may not be in as good a shape as I used to be, but the least I can do to help.

KAREN MORENO: We lost everything. Everything.

JAMIE MORENO: Yeah my mom lost everything. So, it sucks.

MAN: OK, we've got room. We're coming to get you.

WOMAN: I'm worried, I ain't gonna have a place to lay down or nothin.

EAN DUPLANZAN: You'll have a place to lay down, I can take care of that. Look at me. Look at me. I can promise you that.

MAN: Search and rescue, anyone home? We are search and rescue, you all OK?

WOMAN: Yeah we're good.

MAN: If ya'll need to get out now's the time.

JAMAR CRISWELL: Wasn't no running water no electricity, so we started dipping buckets to flush toilets and stuff. I was ready to get out of here.

WOMAN: It had already gotten up to the furniture in the living room. And I'm sure that my bed and my television, all of this is gone.

MAN: Watch that curb guys, fire hydrant.

JAY DILLON: We were dispatched to a house on fire and was surrounded by three feet of water. The only thing we could do was connect a hose directly to the fire hydrant, which was underwater. We had a little bit of challenge finding the hydrant that was underwater. Once we were able to find the hydrant and connect to it we got our initial hose line on there and we basically just protected the exposure surrounding the house. It was burning. It was nearly fully involved when we arrived.

MAN: Fire, I mean they're keeping it off of the (inaudible), but we just don't have enough water pressure.

TWYLA LADAY: Everybody on the bottom floor were evacuated or they left, but we tried to stick it out on the second floor because we were on the second floor, but the water kept rising. So we had to get really just leave when the police officers came by.

GLORIA ANDERS: Just like that we went in and before we can do anything the water had already gushed into the house. And I said well y'all we can't stay here so. And it was coming up higher and higher. I lost everything, everything. I lost stove, refrigerator, food. We had just grocery shopped and just filled up the deep freezer for the month. And we lost everything.

MAN: Clothes, shoes, furniture. I gotta start all over again.

WOMAN: Our apartment, we had over six feet of water. My car, I lost it. This is a truck and this is my car here underwater.

WOMAN: I lost everything. And I was praying and hoping that it wasn't going to be this bad, but it was.

AMBREEN RAJAN: We opened the door and looked inside. It was all broken. The smell is really bad. It's really, really, really bad. I mean, I can't even breathe. I was about to throw up. A lot to clean up. The whole city is a mess right now. It's a mess.

YASMIN MEDRANO: I came inside and the first thing that I went to see my room. I was like, oh my room. It was the first one to get flooded, my room. The water started coming from my room first. So I went inside and it was still water in there. And I was like wow. And all my clothes they were just on the ground. My bed, it up to my bed. Everything got ruined. I was, I started crying because it was really bad.

AUSTIN FINEFROCK: The water damage, you can see the line. It was about two feet up in here. It happens. Stuff happens, you know, but everyone's all right, everyone's safe. You know my family's safe, my kid's safe. So we're just on to the next phase of what happened.

OPAL RODRIQUEZ: We care about each other. We love each other. And when things get hard, we all come out, hundreds and thousands, to help each other.

JAMES MCBRIDE: I'm 50 years old, and it's enough to make you cry. It's amazing to see. A lot of people come out and help those that are, that are in need. Had it not been for the volunteers, a lot of people probably would have lost their lives.

NATALIE MOTT: And we're going to get through this. We got through Katrina and we're going to get through any other storm, anything that comes our way.

LUIS CARTDENAS: I've lived here all my life. And with this disaster coming, it was just amazing how people have stepped out, you know, to help.

NOEL GEER: It's the best part of people. And it gives me hope for the future that, you know, people are able to come together for this and that we're more alike than we are different.

CJ BROWN: People coming down from Dallas, from Austin, and San Antonio, you know, just to, you know, spend their life to help us, you know, regroup, and you know get back on our feet again and start going.

ANDRE AZIZI: People care more than you think. And people are more resilient than you think.

Hurricane Irma, September 2017

Irma arose rapidly in the tropical Atlantic, and at one point it had sustained wind speeds of 185 mph. This storm intensified rapidly, which is a characteristic of a large hurricane, increasing by 45 mph in one day. hit the islands of Barbuda, Antigua, St Martin and St. Barthelemy and caused catastrophic damage in these locations. The island of Barbuda, in particular, was literally flattened. Irma next set her eyes on Cuba, where it came ashore as a magnitude 5 storm with sustained winds of 160 mph and a massive storm surge. The storm led to collapsed buildings and flooding of coastal areas including the historic Malecón in Havana. Fortunately, Cuban authorities had evacuated close to a million people from low-lying areas.

A few kilometers make a major difference in the history of a hurricane and the landfall in Cuba, which was not initially predicted, weakened the storm significantly. Initial forecasts were for Irma to come ashore near Miami with wind speeds near 155 mph, but the storm tracked a little further to the west and made landfall in the Florida Keys with maximum winds of 130 mph, then again in Marco Island on the west coast of Florida with winds of 115 mph. As it turns out, there have been far larger storms in Florida, including Hurricane Andrew in 1992, which flattened the Miami suburbs. But Irma was yet another reminder of how vulnerable the state is to storms. Much of the southern half of Florida is a natural swamp or marshland that originally looked like the Everglades National Park. But as in Houston, commercial interests, and in the case of Florida, the desire of citizens to own a small piece of paradise, have led to massive construction in the last decade, runaway development with insufficient environmental regulation. So, instead of swampland that served to absorb moisture and drain it back towards the ocean, large expanses of concrete funnel it into walls of water in cities and suburbs. Mangroves forest that previously protected the coast has been flattened. In fact, the Florida environment was destroyed a long time before this, as the Army Corps of Engineers modified the natural drainage to provide water for the sugar industry.

As it turns out, Irma was less of a wind event than a storm surge event. As a hurricane moves towards land, it pushes water ahead of it, literally a wall of water. The result is storm surge. Hurricane Katrina in 2005 was also a storm surge event, with a surge of 28 feet measured at Pass Christian, Mississippi, just outside of New Orleans, the largest surge ever measured in a US hurricane. New Orleans is at or even below sea level and its levee system, upgraded after Katrina, is designed to deal with surge, but still, it remains highly vulnerable. The surge from Irma was about 10 feet in the Keys and Marco Island, enough to cause significant damage. Nevertheless, the storm was generally viewed by experts as another wake-up call to what will likely happen in the future if a major storm with winds over 160 miles an hour and a 20-foot storm surge hits Miami or Tampa which is extremely flood-prone. In all, Irma caused over 100 fatalities, most of which were in the Caribbean.

Hurricane Maria, September 2017

Barely a week later, monster storm Maria developed as Irma had…this storm also developed by rapid intensification with an increase in wind speed of over 60 mph in one day! By the time it hit Dominica, Maria had sustained winds of 160 mph and it caused utter devastation and killed 15 people, then it took aim at Puerto Rico. The storm hit the east coast of the island with sustained winds of 155 mph and dumped up to 3 feet of rain in mountainous areas. The impact on Puerto Rico is like the combined effect of Harvey in Houston and Irma in Barbuda. Maria caused massive destruction on the island. The power grid was destroyed leaving all 3.4 million residents without electricity. Many people had no running water for days, and sewers and cell phone networks were also out. Dams were in danger of breaching. 60,000 homes lost most or all of their roofs and only 392 out of 5000 miles of roads remained open. The storm defoliated a large number of trees on the island and led to the loss of 80 percent of the agriculture. The total damage is estimated at $90 billion, but that does not include the misery the storm caused humans. Diseases spread due to the lack of clean drinking water. The water-borne bacterial infection leptospirosis was widespread. Overall, the storm directly or indirectly led to as many as 3000 deaths but the true number may never be known, and, years later, the island is still recovering from the storm.

Hurricane Dorian, September 2019

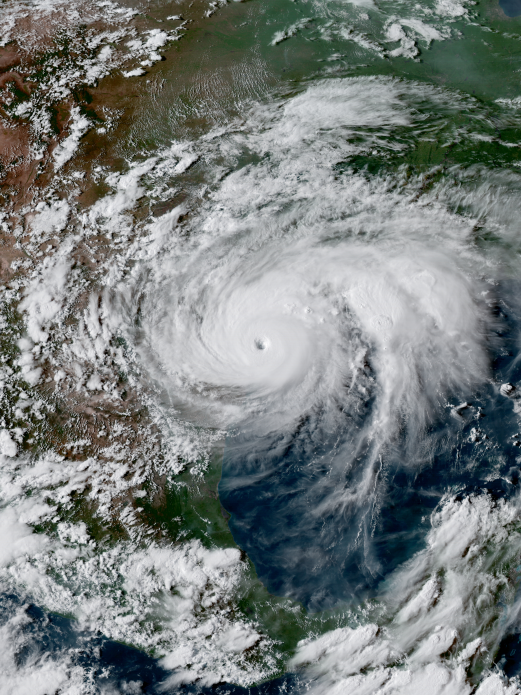

None of these storms compared to Dorian that hammered the Bahamas in 2019. Dorian made landfall on September 1, 2019, on Grand Abaco Island with sustained winds of 185 mph and gusts over 220 mph making it one of the strongest storms on record in the Atlantic and Pacific.

Dorian was an unusual storm in several ways. The storm was enormous. Dorian was particularly deadly because the devastating winds were combined with an extremely slow forward motion of about 5 mph so that the storm ravaged the Bahamas for days. Devastating storms like Andrew and Katrina had much faster motion but the slow speed of Dorian made the damage much, much worse. After pummeling the Abacos, a group of islands in the northeast Bahamas, the storm went back over open water and made landfall without weakening on September 2 on Grand Bahama, the largest Bahama island, where it literally stalled for a day before weakening a little and moving back over open water. The damage to the Bahamas was truly catastrophic.

At landfall on the Abacos and again on Grand Bahama, Dorian’s intense winds were accompanied by a massive storm surge of about 6-9 meters (20-25 feet) and heavy rain. In total about a meter (3 feet) of rain fell over most of the northern Bahamas. There are harrowing tales of people clinging on to trees and other harrowing survival stories, but sadly many were not so fortunate. The official death toll from Dorian is 70 but is almost certainly much, much higher because there were many undocumented citizens living in shantytowns. Initially, there were over 1000 people missing, and now that number is around 300, so the death toll is likely to be 500-600. The true number may never be known.

Hurricane Ian, late September, 2022

Now to Hurricane Ian that hit southwest Florida in late September 2022. The storm was notable because of how rapidly it intensified, with windspeeds increasing from 75 mph to a 155 mph in just two days. The very large storm came ashore at Cayo Costa island just to the north of Fort Myers on September 28th 2022. Sustained windspeeds at landfall were 150 mph likely with higher gusts. It was the fifth strongest storm ever to hit the 50 contiguous states.

But the damage in southwest Florida was not just inflicted by the wind. Since the path of the storm closely paralleled the coast as it approached land, and because the highest surge is in the right front quadrant of the storm due to its counter-clockwise circulation, the storm surge over large areas was devastating.

The storm surge was between up to 15 feet above normal sea level along the barrier islands of Captiva, Sanibel and Fort Myers Beach. This wall of water caused massive devastation in these areas as observed in the photographs below.

Ian moved slowly to the northeast direction across the Florida peninsula and this slow path caused heavy rainfall over a wide area, with precipitation totals up to 17 inches over a 12-24 hour period. This rainfall caused widespread flooding well inland in places such as Orlando.

One of the main stories of the storm was prediction. The different forecast models agreed closely as the storm approached southwest Florida, but because the path was so close to parallel to the coast a small change led to a major difference in the landfall location. Two days out the path was more northerly with the eye forecasted to make landfall near Tampa, but then a day out a minor jog in the forecast to the east shifted the eye well south. This change led to some delays in evacuation in the Fort Myers area.

The storm caused massive damage over a widespread area with catastrophic damage to housing along the coast, especially in Fort Myers, Sanibel Captiva and Port Charlotte. More than 2.7 million people lost power at the height of the storm and a large number without clean water. Overall the storm led to 136 fatalities in Florida and a total of $50 billion in damage.

Hurricane Helene, September 2024

Hurricane Helene arose as a depression in the Caribbean. The storm rapidly intensified over the unusually warm Gulf of Mexico as it moved towards the Big Bend region of Florida where it made landfall on the evening of September 26, 2024, as a category 4 hurricane with sustained winds of 140 mph. The hurricane was also very large and had a high storm surge along a long area of the western Florida coastline from about 10 feet in the Big Bend to about 7 feet in the Tampa Bay region, causing extensive flooding along the whole coast.

Since the storm was moving so rapidly it maintained its strength inland and it was still a hurricane when it hit southern Georgia. Wind damage was severe well inland in both states.

Helene was still a tropical storm when it moved across northern Georgia near Atlanta, South Carolina near Greenville, and North Carolina near Asheville. In these regions, some damage was caused by wind, but most of it was done by water. A stalled frontal boundary had dumped up to 9 inches of rain over the mountains of western North Carolina before the storm arrived. The ground was therefore already saturated when the storm arrived, and this led to extensive tree damage from tropical-storm-force winds. Rainfall totals of up to 32 inches in the mountainous terrain caused many landslides and mudslides. The water rushed down the hillslopes causing rivers to rise rapidly, and overflow their banks leading to extensive flash flooding. River levels were at record levels, for example, the French Broad and Swannanoa rivers in Asheville were up to 5 feet above historic levels, breaking a record set in 1916. The results were absolutely catastrophic in Asheville and small mountain towns all over western South Carolina, North Carolina, and Tennessee. Extensive flash flooding swept away single-family homes and mobile homes, and flooded businesses.

The most dire result of Helene was loss of life. The storm was the most deadly since Hurricane Katrina with over 280 dead. Over 100 of these deaths occurred in western North Carolina, where many more are still missing at the time of writing. The storm was also the costliest since Katrina with estimates of over $50 billion with billions of dollars of uninsured flood damages.

Hurricanes and climate change

So, finally, we come back to the question of whether climate change is responsible for the surge in powerful hurricanes in 2017-2022. At the outset, we must stress that this question cannot be answered unequivocally. However, there are several factors that make it safe to say that large storms will be more common in the future and that they will cause increasing amounts of damage. To develop, storms need warm temperatures (over 80 degrees), abundant moisture, and circulation, as you can see in the video below.

Video: Fuel for the Storm (2:19)

As we will see in the lab at the end of this module, the ocean has warmed by 1 to 2 degrees C (3-4 degrees F) over the last century, and this leads to a 12-16 percent increase in moisture (3% per degree). Thus, there is a lot more fuel for hurricane development. The formation of hurricanes is also helped by weather disturbances often off West Africa, but there is not yet a relationship between these events and climate change.

In the case of Harvey, the volume of water is clearly a result of an extra warm ocean; for Irma and Maria, the ferocity of the winds and the rapid intensification is also related to water temperature. For Dorian, size and slow movement is a result of a warmer atmosphere. So, climate change is adding fuel to the fire for large hurricane development, and 2017 is a harbinger of things to come. There is one other factor to consider, perhaps one that will prove the most devastating in decades to come. Sea level rise. The ocean is now about a foot higher than it was in 1900. Projections are for a possible 6-foot rise in sea level by the end of this century if we don’t cut greenhouse gas levels significantly. We will discuss the issue of sea-level rise in great detail in Module 10. Such a rise would mean that even a storm such as Irma with a moderate storm surge would be catastrophic.

As with other impacts of climate change, the latest IPCC report stresses the need for adaptation to the threat of stronger hurricanes. Coastal communities will need to adapt to this threat by building homes higher and stronger, building sea walls and surge barriers, and gradually pulling back from the coast, an initiative called managed retreat. This is already happening near New York City and elsewhere in the US but again will be much more difficult to achieve in the developing world.