Mountain Glaciers

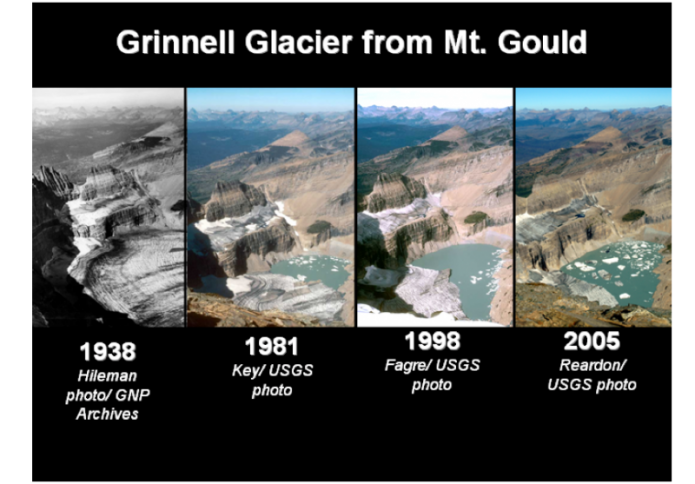

We’ll start with some striking images taken by glaciologists around the world — these are photos of mountain glaciers taken from the same spot at different times, and they provide us with some fairly shocking observations on just how much glaciers can change and have done so recently.

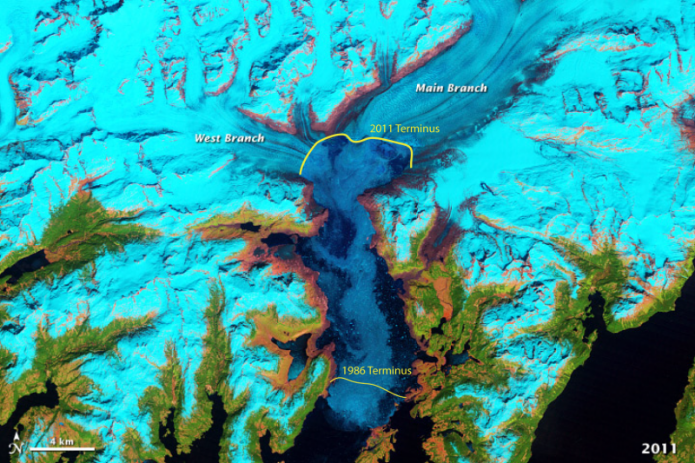

For another Alaskan example, we turn to satellite imagery of Columbia Glacier, which obviously does not reach back into time as far, but nevertheless, there are some dramatic changes evident here:

The above scene is from 1986, and at this point in time, the end of the glacier (terminus) is located down near the bottom of the image. Below, we jump forward in time to 2011:

As you can see, the terminus here has retreated by about 15 km in just 25 years — a very impressive rate.

Grinnell Glacier, in Glacier National Park, Montana, as seen from the same vantage point over a 67 year period. The glaciers in this famous national park are all in such rapid retreat that the park may need a new name in a few decades.

Glaciers in the Alps are shrinking too. Check out SwissEduc Glaciers online to see one good example — at the bottom of the page is a comparison that flips back and forth from the past to the present as you move your mouse over the image.

The same story as seen in Alaska, Montana, and the Alps holds for glaciers in more tropical settings, as can be seen from the images of Qori Kalas glacier in the Andes Mountains of Peru, below.

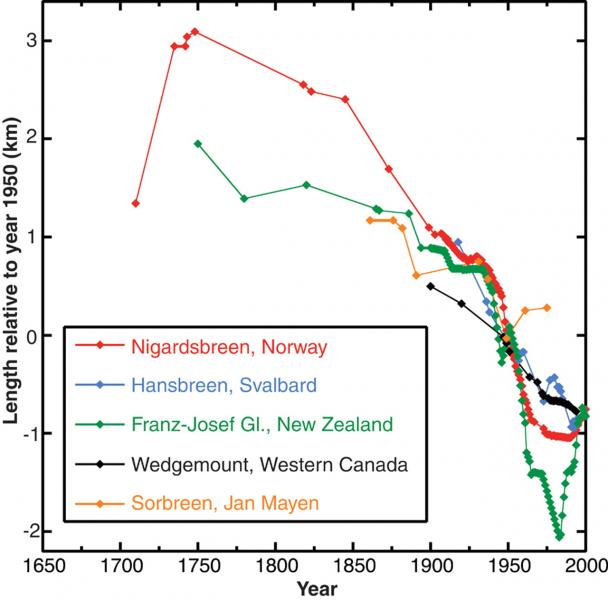

Studies of glaciers around the world show that an overwhelming majority are losing mass over time. In most cases, this loss of mass is reflected in the glaciers' retreating, so the length of the glacier becomes smaller. The figure below shows a selection of data from glaciers around the world, documenting this pattern of retreat.

This image is a scatter plot showing the retreat of several glaciers over time, titled with the data points representing the length of glaciers relative to their 1950 positions. The glaciers tracked are from different regions, and the data spans from around 1650 to 2000.

- Graph Type: Scatter plot

- Y-Axis: Length relative to 1950 (km)

- Range: -2 km to 3 km

- X-Axis: Years (1650 to 2000)

- Data Representation:

- Nigardsbreen, Norway: Red line with dots

- Starts at 3 km in 1650, steadily decreases to around 0 km by 2000

- Hansbreen, Svalbard: Blue line with dots

- Starts at 1 km in 1900, decreases to around -1 km by 2000

- Franz-Josef Glacier, New Zealand: Green line with dots

- Starts at 0 km in 1900, fluctuates, and ends around -1 km by 2000

- Wedgemount, Western Canada: Black line with dots

- Starts at 0 km in 1900, decreases to around -1 km by 2000

- Sorbreen, Jan Mayen: Orange line with dots

- Starts at 0 km in 1900, decreases to around -1 km by 2000

- Nigardsbreen, Norway: Red line with dots

- Trend:

- All glaciers show a general retreat (negative length change) over time

- Nigardsbreen has the longest record and most significant retreat, losing about 3 km since 1650

The scatter plot illustrates a consistent retreat of glaciers across different regions over the past few centuries, with a notable acceleration in retreat since the 1900s.

The vast majority of glaciers on Earth are melting, and this melting began about the time that the temperature records indicate the beginning of warming, around the beginning of the 1900s.

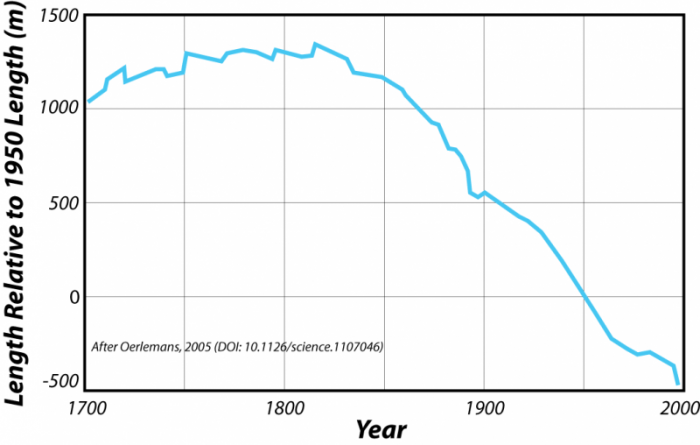

If you combine the records of glacier length changes from around the world into one graph, we can get a pretty clear idea of what is happening.

This image is a line graph showing the retreat of a glacier over time, with the data representing the glacier's length relative to its 1950 position. The graph is sourced from a study by Oerlemans (2005), published in Science (DOI: 10.1126/science.1107046).

- Graph Type: Line graph

- Y-Axis: Length relative to 1950 (meters)

- Range: -500 m to 1500 m

- X-Axis: Years (1700 to 2000)

- Data Representation:

- Glacier Length: Blue line

- Starts around 1200 m in 1700

- Remains relatively stable with minor fluctuations until around 1850

- Begins a steady decline after 1850

- Drops to around -500 m by 2000

- Glacier Length: Blue line

- Trend:

- Stable length from 1700 to 1850

- Significant retreat (about 1500 m) from 1850 to 2000

The graph illustrates a clear and consistent retreat of the glacier over the past 150 years, with the most significant length reduction occurring after 1850.

On the graph above, the y-axis plots the length of the glaciers relative to their length in 1950 — so this is a kind of length anomaly. A positive number means that on average, glaciers were longer than they were in 1950; negative numbers mean they were shorter. Here, we can see that beginning around 1850, glaciers around the world begin to shrink, and this trend continues to the present. The average glacier has retreated almost 2 kilometers in this time.

It is possible to estimate the magnitude and history of temperature change needed to produce this history of glacial retreat, and Oerlemans (2005) did this using a simple model; the results are shown below.

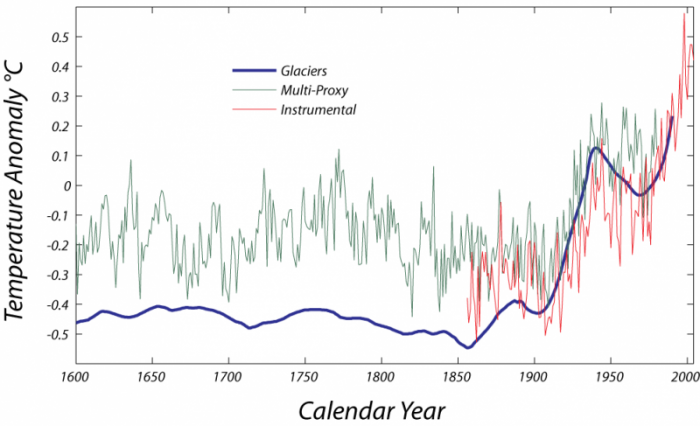

This image is a line graph showing global temperature anomalies from 1600 to 2000, derived from three different data sources: glacier records, multi-proxy reconstructions, and instrumental measurements. The anomalies are measured in degrees Celsius relative to a baseline.

- Graph Type: Line graph

- Y-Axis: Temperature anomaly (°C)

- Range: -0.4°C to 0.5°C

- X-Axis: Calendar years (1600 to 2000)

- Data Representation:

- Glaciers: Blue line

- Starts around -0.3°C in 1600

- Remains relatively stable with minor fluctuations until 1850

- Rises sharply after 1850, reaching about 0.4°C by 2000

- Multi-Proxy: Green line

- Starts around -0.2°C in 1600

- Shows more variability, with fluctuations between -0.3°C and 0.1°C until 1900

- Rises after 1900, reaching about 0.3°C by 2000

- Instrumental: Red line

- Starts around 1850 at 0°C

- Shows high variability, with peaks and dips

- Rises steadily after 1900, reaching about 0.4°C by 2000

- Glaciers: Blue line

- Trend:

- All three datasets show a general increase in temperature anomalies after 1850

- Glacier and instrumental data align closely in the 20th century, showing a sharp rise

The graph illustrates a significant warming trend in global temperatures since the mid-19th century, with all three data sources confirming a rise of about 0.4°C by the year 2000.

The thick blue line here is the temperature history needed to produce the timing and magnitude of the glacial retreat history shown in the previous figure. For comparison, we also see the instrumental temperature record in red (Jones and Moburg, 2003) and the temperature reconstruction based on multiple climate proxies (Mann et al., 1999). Note the excellent match with the instrumental record in the last century.